1A in Action: Kate Lindley and Speaking Out About Book Access

Kate Lindley grew up fostering a love of books and reading. She read the “Harry Potter” and “Chronicles of Narnia” series at a young age and joined a Reading Olympics team through the library, where she read 30 to 40 books a year. She calls that experience “one of the most important things I’ve done in my life.”

That early love of books, reading and libraries is why she took note – and action – in June 2023 when the school board in Hanover County, Virginia, removed 19 books from libraries and classroom instruction in all county schools. The books were removed under a newly passed board policy that allowed the challenge, review and removal of books deemed “age inappropriate, pervasively vulgar, obscene or sexually explicit,” as Virginia Public Media reported.

The school board later removed over 70 other books from public school libraries, citing “sexually explicit” content.

However, Lindley says the removals included books such as “The Handmaid's Tale” by Margaret Atwood and “Slaughterhouse-Five” by Kurt Vonnegut, books Lindley describes as “very important resources or otherwise very important literature.”

As a high school senior and Girl Scout, she wanted high school students in Hanover County to have access to books such as these and others that she had found useful in learning about the world and herself.

With her computer coding skills, Lindley made an app for students to learn more about the books and why they were removed. She was working on her Gold Award, the highest honor for a Girl Scout, and the project became part of that effort.

Lindley decided students needed more than just information about the removed books; they needed to see the books to make an informed decision for themselves. She set up an Instagram account to spread awareness and solicit book donations. She gave the donated books away to high school students in Banned Book Talk Totes that included some of the removed titles as well as discussion questions on the books.

The popularity of the project prompted Lindley to take the project further by creating Banned Book Nooks in local businesses, which made the books removed by the school board available to anyone who wanted one. They operate similar to free little libraries in people’s yards. The books are free for anyone to take and don’t have to be returned. She inserted stickers in the books with QR codes for people to leave reviews.

Editor's note: This profile is part of an ongoing series, “1A in Action,” which highlights individuals who fought for their — and other people's — First Amendment freedoms.

What’s at stake:

The First Amendment’s free speech clause means books are protected from government censorship unless they fall into an unprotected category of speech because they are, for example, obscene or defamatory.

Public schools can remove books from classrooms and libraries based on educational appropriateness for age and grade levels, but there is no national standard (or U.S. Supreme Court ruling) that neatly spells out what those standards are for each age and grade. Decisions often involve public input, including by parents and other members of the community who use their First Amendment right of petition to ask a school board to remove books from schools or to weigh in when the school board or school administrators themselves set the process in motion by identifying a book for removal.

RELATED: 1A in Action: Cindy Martin and Advocating for the Right to Speak at School Board Meetings

However, students are generally free to bring personal copies of books to public schools even if the school board has removed them from the library or formal classroom instruction.

What happened:

Since Lindley’s project was for her Girl Scout Gold Award, she was set to be honored through an official proclamation by the Hanover County Board of Supervisors with other Gold Award and Eagle Scout honorees in the county. But the board opted to suspend such proclamations, according to Lindley. After community pushback, Lindley said the board reinstated the proclamations, but they did not read the full description of her project and removed words like “banned” from the description when giving a public congratulatory proclamation about her project. For example, the formal proclamation said her project built “Book Nooks” in stores, editing their official name: Banned Book Nooks. Lindley also said the county board of supervisors did not reference the school board’s action to remove the books, the very impetus for her project.

Lindley exercised her freedom of speech and petition during the formal public comment period at the board of supervisors meeting to read her official project description about censorship and book removal by the school board.

The situation made news headlines. The Freedom to Read Foundation gave her an award.

What Kate Lindley says:

Lindley says she is “very happy it happened that way,” as it brought more attention to her project and what she believes is the need to fight for open access to information.

“I read (the project description) out and told them the truth, which is that they had honored me in the best way anybody can when your project is about censorship: They censored me,” she says. “That shows that they are truly afraid of what my project meant and of actually acknowledging what they had done.”

Why it matters to you:

The First Amendment protects your right to access information, including by reading books. You also have the right to speak up about book removals if you disagree with them – whether in front of your school board, a county or city council, or another group that oversees policies.

But the First Amendment’s freedom of petition includes the right to ask school boards to remove books from classrooms and libraries based on educational appropriateness. And schools and libraries may initiate their own review of their collections to identify books for removal, based on factors such as age and educational appropriateness.

Kate Lindley’s inspiration:

Lindley knows that not everyone shares her view about access to books for students. But she believes her stance on the First Amendment is one that many people hold.

“I believe the First Amendment is one of the things that I think is so intrinsically American, and it's one of the things that I can get the most patriotic about,” she says. “I think it's beautiful that we have the right to disagree. … As long as we disagree in a way which isn't saying the other person just sucks and we hate them forever, I think it's an incredible right that we have been given and that we have fought for time and time again.”

Ask an expert:

There are debates going on around the country about which books should be available in public schools and public libraries. Some people view this purely as a free speech issue that affects the rights of authors and readers. But it’s not that simple. People on both sides are exercising their right to petition as well, which creates a conversation within the “marketplace of ideas” that allows individuals, communities and, ultimately, the decisionmakers to rethink their positions and act after having multiple viewpoints available to them.

– Kevin Goldberg, First Amendment expert, Freedom Forum

Learn more:

There’s a lot to learn about freedom of speech, petition and the First Amendment. Here’s more about freedom of speech and some of its limits. Here’s more on the freedom of petition. And here’s much more about the First Amendment.

Keep in touch:

We’ll come to you. Sign up for our newsletter to get First Amendment news and resources in your inbox every week. And get in touch if you want to share a “1A in Action” story of you or someone you know.

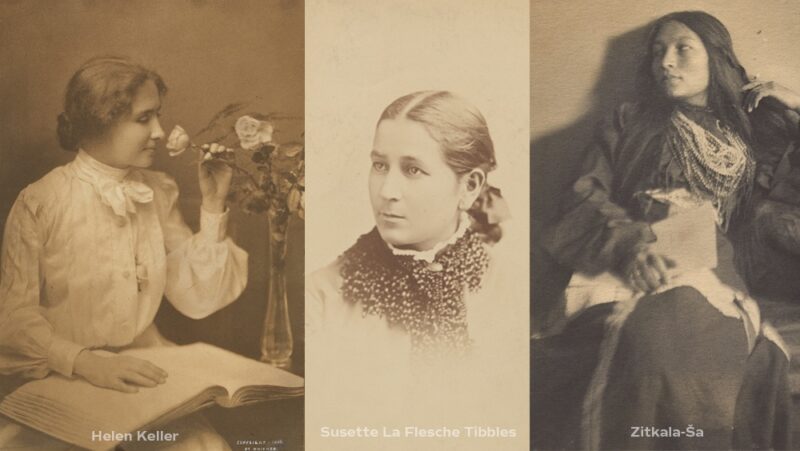

9 Women Who Used the First Amendment to Shape History

What Is Book Banning and Is It Unconstitutional? The Complete Guide

Related Content

Here to top your best dad joke.