25 Black Civil Rights Activists Who Used the Power of the First Amendment

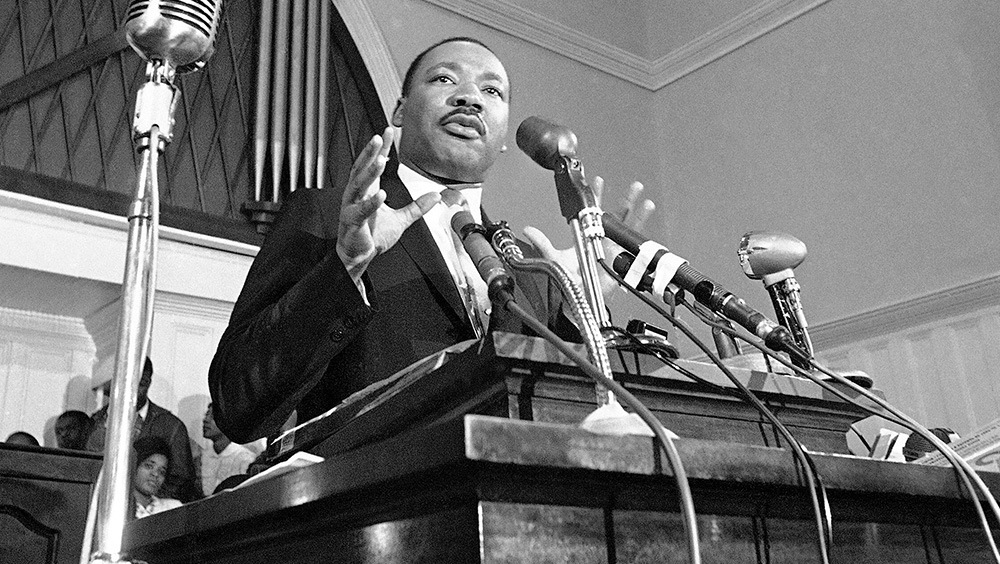

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. tops most lists of influential Black civil rights activists. If there is one person from the Civil Rights Movement who created lasting change, it’s King. Elementary school students learn of his life and legacy, largely through his most recognized words: the “I Have a Dream" speech from the 1963 March on Washington.

King’s words live on as a reminder that the work of advancing civil rights can take a toll. He was assassinated less than five years after making that speech. King’s murder came after he was involved in another march. He went to Memphis, Tennessee, in March 1968 to support and assemble with striking sanitation workers. The city employees were striking to protest poor wages and dangerous conditions following the on-the-job deaths of two Black workers.

The March on Washington and the Memphis sanitation workers strike are significant examples of how King and countless others used their First Amendment freedoms to advocate for civil rights.

Discover 25 Black civil rights activists who used the First Amendment to advance their causes

King may be the most recognized Black civil rights activist in U.S. history, but he is far from the only one. Many others have used similar methods to spread their message for social change and educate people about American history. Many have marched and used their First Amendment freedoms of religion, speech, the press, assembly and petition.

Here are others who, like King, used the First Amendment to advance Black civil rights.

Black civil rights activists during King’s era

As a close friend of King, John Lewis (1940-2020) was a direct connection from the 1960s era of protest to the modern era of political representation. Lewis, who led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was infamously beaten by police during the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. He returned to lead marches and commemorate “Bloody Sunday” as a prominent civil rights figure and long-running member of Congress from Georgia.

Rep. John Lewis speaks on Capitol Hill during a 2013 ceremony in observance of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Less known to history but extremely important to the movement with King and Lewis was Bayard Rustin (1912-1987). He was a close adviser to King and the nonviolent movement. But he was often marginalized or kept out of public discussions in the 1950s and 1960s because he was openly gay. The 1963 March on Washington is largely credited to his organization and leadership. A 2023 movie, “Rustin,” from Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company, brought his historically overlooked contributions to the wider public.

As a young student, Diane Nash was skeptical of the nonviolent approach of King and Lewis. But she accepted it and was a key leader in SNCC’s work and the 1961 Freedom Rides. She led sit-ins at Nashville lunch counters that refused to serve Black patrons. Her direct advocacy helped integrate the restaurants in Nashville ahead of many other Southern cities.

Rosa Parks (1913-2005) and Ralph Abernathy (1926-1990) are closely tied to the Montgomery bus boycott. Parks is remembered for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger, which sparked the boycott. Abernathy was a key organizer and leader of the boycott, which led to a U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in public transportation. Both contributed decades of advocacy and activism beyond the bus boycott. With King, Abernathy co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and became its president after King was assassinated.

Jesse Jackson raises the arm of Rosa Parks at the 1988 Democratic National Convention.

Among the people with King when he was shot was the Rev. Jesse Jackson, a close adviser and friend. Jackson carried the torch of nonviolence and civil rights advocacy into future decades, starting advocacy groups that eventually became the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition. He ran for president as a Democrat in 1984 and 1988. President Bill Clinton awarded Jackson the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2000.

Black civil rights activists who split from the nonviolent movement

King and Lewis were known for their advocacy of nonviolent resistance. But other prominent figures emerged during this time who split from King’s approach and those around him.

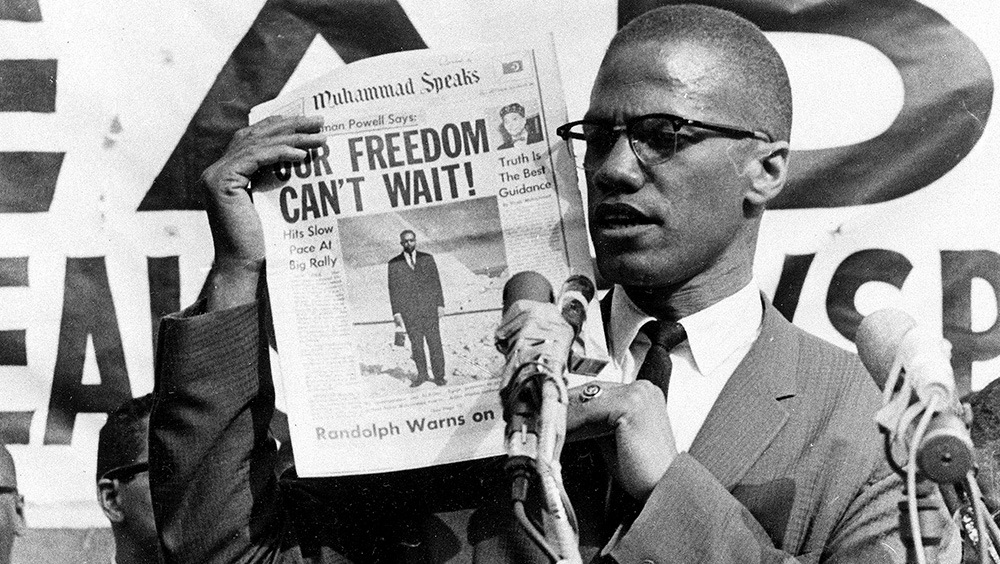

Malcolm X (1925-1965) is likely the best known. A Muslim, he advocated for Black separatism and empowerment within the Nation of Islam. He criticized King’s movement and the March on Washington as a “farce.” But he later distanced himself from and criticized the Nation of Islam. He was assassinated by NOI members in 1965.

Malcolm X holds up a paper for the crowd to see during a 1963 rally in New York City.

The era also led to the founding of the Black Panther Party, which advocated for Black civil rights and empowerment through armed self-defense. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton (1942-1989) are well known as its co-founders, but the group’s leaders included others of note, such as Elaine Brown, the only woman to head the Panthers. She went on to lead a property development project for poor residents of Oakland, California, where she led the Panthers more than 50 years earlier. The name of that housing development: The Black Panther.

The Black Panthers and similar resistance movements called for “Black power.” The term is associated with Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998), aka Kwame Ture. He was aligned with King, Lewis and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee until the mid-1960s, when he began to rethink its methods of sit-ins and peaceful marches. He advocated for a Black political party independent from the Democratic and Republican parties.

Black activists who continue civil rights work today

Advocating for civil rights didn’t end with the death of King or the end of the 1960s. More than 60 years after the March on Washington, people inspired by Black civil rights activists before them continue their work by organizing, assembling, protesting and petitioning for change.

The Rev. Dr. William Barber II continues King’s work leading the Poor People’s Campaign and its commitment to nonviolence. He is president of Repairers of the Breach, a nonprofit dedicated to social change and advancing racial justice.

Voting is one way to advance change and petition the government, and Stacey Abrams has played a major role in ensuring voting rights for Americans following her 2018 run for governor of Georgia. She started the organizing group Fair Fight to help register more people to vote across the country and remove barriers to voting.

Today’s Black civil rights activists are also calling for systemic changes beyond organizing and voting rights. Author, activist and podcaster DeRay Mckesson has advocated for police reform in the years following the 2016 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. He was a prominent figure advancing the Black Lives Matter movement before 2020. He has criticized police action against Black protesters organizing for racial justice compared to the response toward people who attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Police arrest activist DeRay McKesson during a 2016 protest in Baton Rouge, La.

MORE: DeRay Mckesson is a 2021 Free Expression Award honoree

High-profile killings of Black people have spurred calls for reform and legal charges against officers and public officials. Civil rights attorney Ben Crump has been front-and-center representing families in such cases, including the deaths of Tyre Nichols in Memphis, Tennessee, Ahmaud Arbery in Glynn County, Georgia, and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky. These and other prominent cases following George Floyd’s murder brought Crump his legal nickname: “Black America’s attorney general.” It’s a name Crump got from another famous Black civil rights leader: the Rev. Al Sharpton.

People who have advocated for civil rights through writing, music, arts and entertainment

Civil rights activists have used their First Amendment rights to protest and petition to great effect. But activism comes in many shapes and forms – and so does the freedom to express a call for change. Through their words, music, and other creative expressions, people have advanced Black civil rights beyond marching in the streets or on the National Mall.

James Baldwin (1924-1987) wrote about race, gender, sexuality and class through his books, plays and poems. Responding to racial injustice, he left the U.S. for France as a young man. Baldwin returned during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, writing and lecturing about the cause.

Prominent musicians of the 1950s and 1960s like Harry Belafonte (1927-2023) and Nina Simone (1933-2003) worked social activism into their public performances. Belafonte was a well-known club singer of the era and a friend of Martin Luther King Jr., bailing King out of jail in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Simone avoided direct activism in her music in the early 1960s but changed her tune with the 1964 protest song “Mississippi Goddam,” her first of several songs addressing racial injustice.

Harry Belafonte speaks to a crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in 1958.

Outside of music, filmmakers like Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay have translated real-world civil rights history into fictional stories and historical re-telling of major events. Lee’s films have explored the tense topic of race relations since the 1980s with the breakout hit “Do the Right Thing.” He released the biopic “Malcolm X” in 1992. DuVernay received critical acclaim and multiple award nominations for her 2014 King biopic “Selma.” She followed that in 2019 with “When They See Us” about the 1989 case of the “Central Park Five,” who were Black New York City teenagers falsely accused and wrongly convicted of rape.

People who have used press freedom and public platforms

Many journalists avoid calling themselves activists and reject the label from others. Journalists use the First Amendment freedom of the press to highlight injustice and inform the public about social ills and government wrongdoing.

John Lewis praised the work of journalists and connected it to racial justice activism, saying on Twitter in 2015, “Without the brave journalists who covered our protests, the Civil Rights Movement would have been like a bird without wings.”

Earl Caldwell was one journalist with a bird’s-eye view of history at the time. As a Black reporter working for The New York Times, he said he was reluctant to be in the South given the danger there. But he opted to cover King as he went to Memphis in 1968 to support the sanitation workers’ strike. Caldwell was the only reporter on the scene when King was shot, and the first to break the news. Caldwell continued covering civil rights, gaining the trust of Black Panther Party leaders, who were cautious of talking to journalists. The FBI and Department of Justice tried to force Caldwell to reveal information about the Black Panthers, but he refused to testify before a grand jury, citing First Amendment press freedom. His was one of three combined cases that went to the Supreme Court. The justices declined to grant a federal right to protect journalists from giving up confidential information to a grand jury.

Caldwell told the PBS program “Frontline” that he took his job as a journalist seriously, just like he did his identity as a Black man: “It’s just like Martin Luther King Jr. He’s up on that platform talking about the rights of Black people. I can’t separate myself from that because I’m Black, and he’s talking about my rights. I’m a reporter. But reporters are human beings, so we’re faced with these same things every day.”

Nikole Hannah-Jones is known for her work reporting on the historical legacy and effects of slavery, through her Pulitzer Prize-winning work The 1619 Project with The New York Times. In 2016, she co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting to support journalists of color. The name is a nod to pioneering journalist Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), who reported about the lives and lynchings of Black Americans in the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War.

Nikole Hannah-Jones speaks at the 2022 Free Expression Awards.

MORE: Nikole Hannah-Jones is a 2022 Free Expression Award honoree

While not a journalist, Mamie Till Mobley (1921-2003) used the First Amendment’s freedom of the press to advance Black civil rights in a tragic way. In 1955, her 14-year-old son Emmett Till was kidnapped and lynched after a white woman accused him of whistling at her. She insisted that Emmett’s casket stay open to “let the people see what they did to my boy.” With Mamie’s permission, Black-focused Jet magazine and The Chicago Defender published photos of Emmett’s body. Time magazine called it “the photo that changed the Civil Rights Movement.” She continued as a Black civil rights activist and educator in the following decades.

Black civil rights activists and the First Amendment

These people may be well known to history. But there are hundreds, thousands and even millions more who have contributed to advancing civil rights.

That’s because advancing civil rights and using the First Amendment freedoms of religion, speech, the press, assembly and petition aren’t just reserved for prominent activists speaking from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial or leading striking workers in Memphis. Anyone who participates in a march, protest or sit-in, or who votes or writes online is using their First Amendment freedoms.

The specific cause, the message and the methods may differ, but the uniting force is a First Amendment that guarantees these freedoms for all.

Scott A. Leadingham is a Freedom Forum staff writer.

Rick Mastroianni, Freedom Forum’s director of research and library content, contributed background research.

Perspective: Students, Parents and Free Speech Win in Cheerleading Case

Related Content