How Anti-SLAPP Laws Protect Your Right to Free Speech

The First Amendment protects freedom of speech. We are free to speak out on issues we care about without fear that the government will stop us or punish us.

But it can be risky to criticize public figures. Powerful people often have the financial resources to respond to criticism with a lawsuit.

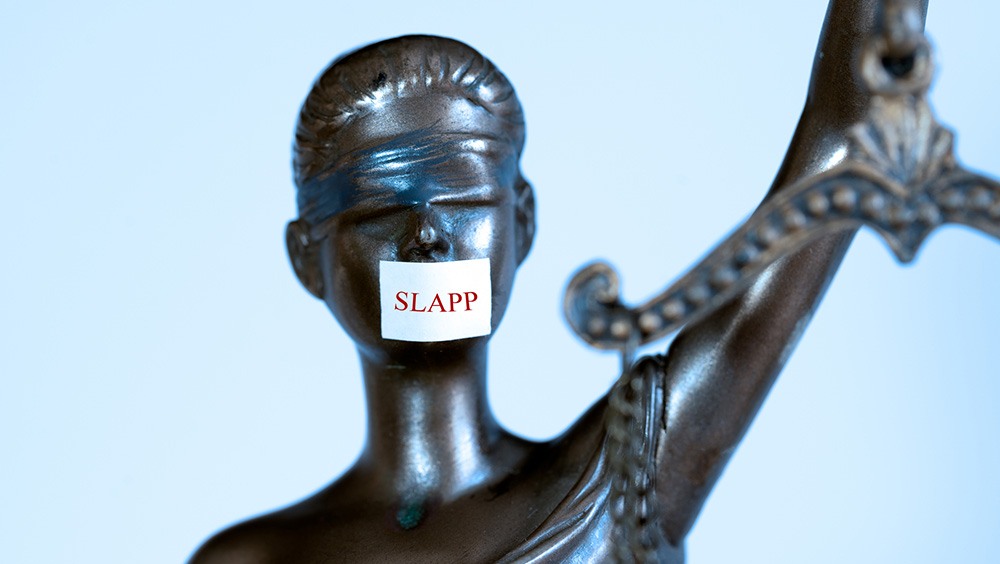

This type of lawsuit is called a SLAPP, which stands for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. The goal of a SLAPP is to get a person to retract their criticism of the person or business. But there are now a growing number of anti-SLAPP laws designed to protect speakers from the threat of going to court to defend their First Amendment right to free speech.

What are anti-SLAPP laws?

Anti-SLAPP laws are designed to protect free speech from being threatened or shut down by people on the receiving end of critical speech. They are designed to prevent SLAPP lawsuits.

What are SLAPP lawsuits?

University of Denver professors Penelope Canan and George Pring created the term SLAPP in the 1980s to refer to a lawsuit whose primary purpose is harassment and intimidation.

The goal is to force someone to take back a critical statement – or not make it in the first place – or else face an expensive lawsuit.

Both the financial and emotional toll are often greater for the defendant than the plaintiff, the person bringing the suit. Most SLAPP suits are filed by powerful people or corporations to protect their reputations against criticism from average people. They are often well-resourced and able to rely on their legal teams to do all the work. Defendants have less money to pay lawyers and must actively participate in their own defense.

How do SLAPP lawsuits affect people’s free expression?

To end or prevent a SLAPP, people will frequently agree to apologize and change their statements and promise not to speak out in the future. This sends a clear message to others who might speak critically as well. The result is the chilling of free speech and healthy debate about important matters of public concern.

Most SLAPP suits are based on claims of defamation or damaging someone’s reputation. But they can also claim a breach of contract, civil rights violations, interfering with the right to do business, or copyright or trademark infringement. They range from complex lawsuits filed in federal court to individual disputes over purely local matters.

How do anti-SLAPP laws protect free expression?

An anti-SLAPP law is designed to prevent SLAPP lawsuits.

Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia have anti-SLAPP laws. But despite repeated attempts, Congress has never passed a federal anti-SLAPP law. People in 17 states, and many people who are sued in federal court, lack protection from SLAPP suits.

Anti-SLAPP laws make it easier for someone who has been sued for exercising their First Amendment rights to get a SLAPP lawsuit dismissed quickly.

More important, anti-SLAPP laws deter people from trying to use lawsuits to silence others. While anti-SLAPP laws vary from state to state, all offer one or more of the following protections:

1. They protect a wide range of First Amendment activities.

Anti-SLAPP laws require that the person being sued show that the lawsuit is targeting their First Amendment rights. Some only apply to statements made in an official government proceeding, like allegations made during a public-school board meeting or in front of the city council. Others apply to any speech on a matter of public concern, no matter where, when or how it occurs. These strong anti-SLAPP laws will also give the speaker the benefit of the doubt that the speech is about a matter of public concern.

2. They put the burden on the person suing.

In most lawsuits, the person being sued can only get the case dismissed in its early stages if they can clearly show they will win; if not, the case can potentially continue for months or even years at great expense.

Anti-SLAPP laws recognize the importance of free speech by putting the burden on the person who is suing to demonstrate why the lawsuit needs to happen. Once the person being sued shows the lawsuit is challenging his or her free speech rights, an anti-SLAPP law requires the person bringing the lawsuit to demonstrate they are likely to win the case. If they cannot do so, the case will be dismissed.

3. They accelerate a final decision.

An initial step in most lawsuits is a long and expensive process where each side collects information from the other in advance of trial. There are often several pre-trial hearings on legal issues. Anti-SLAPP laws pause these time-consuming steps until the court decides who should win.

4. They allow immediate appeal of the initial decision.

Most court cases require that the entire process plays out before the losing party can appeal. Anti-SLAPP laws often say that a defendant can immediately appeal a decision, saving significant time and money.

5. They award attorney fees and court costs to a winning defendant.

The U.S. legal system doesn’t require that a person who unsuccessfully files a lawsuit pay the legal fees and costs of the person they sued. This means successfully defending yourself in a lawsuit is often a hollow victory. Yes, you won but you also had to pay tens of thousands of dollars to win. An anti-SLAPP law says that if the person suing to stop the speech loses, then they must pay the legal fees and court costs of the person being sued.

What are some examples of SLAPP lawsuits?

Some of the biggest First Amendment cases in our history meet the definition of a SLAPP:

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) is considered the most important protector of press freedom. It set the high standard that a public figure filing a defamation lawsuit must show that an allegation made about them was false and that the speaker who made the mistake knew or should have known it was wrong. This standard makes it possible to challenge and criticize powerful people. The lawsuit involved a paid political advertisement in The New York Times designed to raise money for the civil rights movement by criticizing law enforcement response to civil rights protests. It was filed by L.B. Sullivan, Montgomery, Alabama, police commissioner, even though he wasn’t named in the advertisement. Sullivan said that certain facts in the article were incorrect; the paper countered that they were minor mistakes and didn’t matter in terms of the public’s overall view of the treatment of civil rights protesters by southern law enforcement. The lawsuit was filed in Alabama where a jury would be more sympathetic to Sullivan than to the northern newspaper. The jury awarded Sullivan $500,000 to send a message to civil rights activists. But the U.S. Supreme Court later overturned the verdict and protected the newspaper.

- NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co. (1982) also had roots in the civil rights movement. In 1966, a local branch of the NAACP organized a boycott against white merchants who discriminated against Black people in Mississippi. The business owners sued the NAACP. Most protesters’ actions were protected by the First Amendment, but a few people took unprotected actions like threatening store owners. A Mississippi court ruled for the business owners, ordering the NAACP to pay $3.5 million in damages. It took 16 years before the Supreme Court overturned that verdict, saying “the boycott clearly involved constitutionally protected activity” designed “to bring about political, social, and economic change.”

Most SLAPP suits involve everyday speech by average people:

- In 2003, the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition picketed several buildings in New York where tenants lived in terrible conditions. Instead of fixing the problem, building owners sued the NWBCCC for trespass, libel and wrongful interference with business relationships. The court cases went on for several years. They were eventually dismissed but cost NWBCCC more than $1 million in legal fees and forced the organization to focus on defending the lawsuit rather than advocacy efforts.

- In 2010, college student Justin Kurtz’s car was towed from his apartment complex. He started a Facebook group called “Kalamazoo Residents against T&J Towing,” which criticized the towing company’s aggressive practices. T&J Towing filed a lawsuit seeking $750,000 in damages from Kurtz for alleged defamation. The lawsuit lasted eight months before Kurtz and the company decided to resolve their case on their own, out of court. Kurtz was not reimbursed for his legal fees but did exact some measure of revenge: the case went viral with The New York Times eventually publishing a front-page article and the Facebook group grew to 14,000 members.

- In 2010, the Washington City Paper, a free weekly newspaper, published an article that catalogued many alleged wrongdoings by Dan Snyder, the then-owner of Washington, D.C.’s professional football team. He was not amused and filed a defamation lawsuit. Snyder’s lawyers warned the corporate owners of the City Paper that “the cost of litigation would presumably quickly outstrip the asset value” of the newspaper. This letter, in effect, said it would be easier for the City Paper to apologize and go away than stand by its story. The paper did just that, and Snyder eventually dropped the lawsuit.

- In 2019, then-Congressman Devin Nunes filed – and lost – a lawsuit against Twitter and the creators of two parody accounts “Devin Nunes’ Cow” (a mocking reference to his family farm) and “Devin Nunes’ Mom.” Nunes lived in California but filed his lawsuit in Virginia, where there aren’t anti-SLAPP laws. He demanded $250 million. He lost but has filed several different lawsuits since 2018 seeking more than $900 million from those he believes has wronged him. To date, he has not won any of them.

What are some examples of anti-SLAPP laws that protected free speech?

Anti-SLAPP laws have successfully protected speakers in a variety of cases throughout the country:

- In 2003, a Baltimore developer tried to sue future tenants for $25 million after the tenants criticized changes to building plans. The lawsuit was dismissed under the Maryland anti-SLAPP law.

- In 2015, Robert and Michele Duchouquette posted an unfavorable review of Pets for Care on Yelp. The pet-sitting company sued for defamation and for violation of a clause in their service contracts that says clients cannot make negative comments about them. Pets for Care sought up to $1 million and removal of the negative review. Using the Texas anti-SLAPP law, the Duchouquettes got the lawsuit dismissed. They were reimbursed for more than $23,000 in legal fees and other costs.

- In 2017, Phoenix business owner Charlie Lai criticized commercial property owner True North’s remodeling plans. True North tried to sue. Lai used the Arizona anti-SLAPP law to get the lawsuit dismissed, and the court ordered True North to pay his attorney fees.

Anti-SLAPP laws and the First Amendment

While the First Amendment provides strong legal protection for a free press and for our rights as individuals to speak, assemble and petition the government, when a lawsuit challenges these freedoms, it can get costly. Anti-SLAPP laws serve as a great equalizer. They protect those who might otherwise have to self-censor in the face of legal threats. They allow us to speak out on matters that affect our everyday lives.

Kevin Goldberg is the First Amendment specialist for the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

Why Is Christmas a Federal Holiday?

1A in Action: Elle DeLeonibus, the Power of Petition — and Chickens

Related Content

The First Amendment gives all year.

Support the Freedom Forum’s First Amendment mission this Giving Tuesday.