Jan. 6 Won’t Shake my First Amendment Convictions

On the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, I set out from the front steps of my house for a run, exactly 1.24 miles from the U.S. Capitol. I intentionally chose a route to pass by both the East Grounds of the Capitol and the Supreme Court. The “Stop the Steal” rally had not begun in earnest, but I didn’t like what I saw. My initial thoughts included:

“Wow, there are a lot of people here already.”

“There should be a lot more security.”

“Why do I see smoke coming up from the ground in various places? I’ve never seen that before.”

I continued my run, crossing paths with a friend who was headed out to see what was happening. I mentioned my concerns and told him to be careful. I distinctly remember saying, “I have a feeling things are going to get really bad after Trump speaks.”

Jan. 6 will forever stand alongside a select few dates in American history. Images of rioters at the Capitol building in a failed attempt to overturn the election of Joe Biden as the 46th president of the United States will forever be burned in our brains.

For Washington, D.C., residents like me, concerns over the balance between freedom and safety went beyond the philosophical. By early afternoon, we received urgent messages to pick up our children from school as soon as possible. We hunkered down in our homes hoping the mayhem would quickly be contained, emerging to a form of lockdown. Road closures hindered our movement for days; tall fences prevented our usual enjoyment of the Capitol grounds themselves for weeks.

But what sets this date apart is its profound psychological impact resulting in serious soul-searching about our core values as a nation.

As we approach the first anniversary of that day, individuals have been criminally charged, convicted and sentenced. The broader systemic review of identifying the genesis of the violence and whether it could have been prevented has lagged. Each day brings questions as to what the ramifications might be for the future of the free and fair elections that are the cornerstone of our democracy.

And personally, I’ve harbored significant anguish in wondering whether the First Amendment’s rights of freedom of speech, assembly and petitioning the government for redress of grievances were given too much protection that day.

There is a point where protected protest ends and violence begins; the former receives constitutional protection while the latter does not. Even within the former, there are limits: The government can restrict assembly by employing limited “time, place and manner” restrictions that still allow the assembly to occur. It can even shut down protests when presented with an immediate danger that otherwise cannot be avoided. In each instance, the government bears the burden of justifying any restriction.

But after two years of high-profile protests that sometimes included rioting, looting and property damage, is there any wiggle room in where these lines are drawn, particularly when law enforcement can and should step in?

For instance, should access to the Capitol grounds be more limited overall, like it is across the street at the Supreme Court? More broadly: Should our view of an “immediate danger” to public safety change given these violent protests and the speed with which they arise?

After a year of internal reckoning, my answer to all these questions remains a resounding “NO.”

The First Amendment allows only clearly defined and limited regulation of speech for a reason: No matter where the lines are drawn, there will be attempts by government officials to overstep.

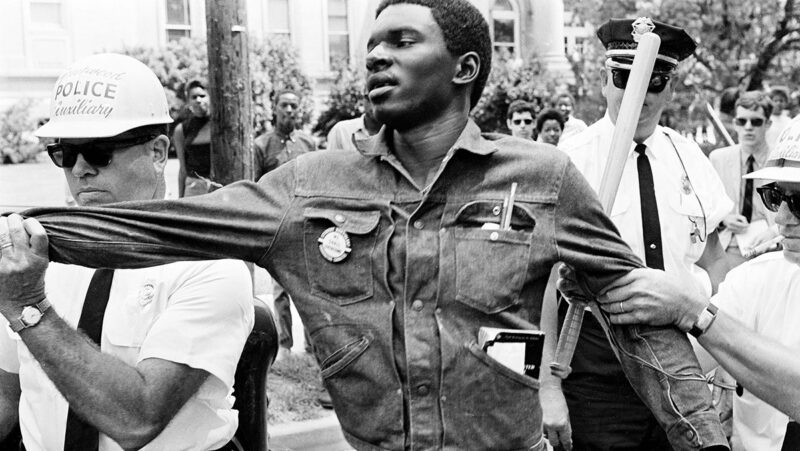

Allowing regulation of speech anywhere short of the standard of “incitement to imminent lawless action” may prevent violence, but it will surely censor protected speech too. This is particularly true for those traditionally lacking power, such as minority groups and fringe voices who often rely on a strong First Amendment to express their distinct views and for whom social media may be a great amplifier. As Freedom Forum Fellow Charles Haynes recently told me: “Freedom of assembly doesn’t mean anything if you can’t practice it because of your race.”

The answer instead lies in ensuring that adequate law enforcement are present and understand their explicit purpose is to protect the right of assembly first and foremost. They should be trained to identify danger signs and to act swiftly and in a targeted manner when violence or clearly illegal, non-speech behavior occurs. And those who are arrested for violent crimes should be punished to the full extent of the law. All enforcement, however, should occur after protest ends and violence begins.

Ben Franklin famously said, “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” Words to heed as we reestablish our core values.

Kevin Goldberg is First Amendment specialist for the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

10+ of the Most Prominent Sports Protests of All Time

Related Content

2025 Al Neuharth Free Spirit and Journalism Conference

All-Expenses-Paid Trip To Washington, D.C.

June 22-27, 2025

Skill-Building

Network Growing

Head Start On Your Future