Art Censorship: First Amendment Violation or Private Free Speech?

Art is in the eye of the beholder, right? After all, one person's modern interpretation of art and its power of social commentary is another person's blank canvas. Seriously, that literally happened.

People may argue over what qualifies as art. What's not up for debate is that all art, including painting, sculpture, dance and provocative exhibition, is free speech protected from government censorship by the First Amendment. But as with all speech, there are some limits.

In this post, we take a deep dive into art censorship. We take a look at how it applies to free speech and the First Amendment, give 10 prominent examples of art censorship from throughout history, and explore the question: What makes art, art?

Art censorship and the First Amendment

Art comes in many forms. For example, depending on your perspective, graffiti on buildings or highway overpasses may be an eyesore or a form of public art that should be protected. The same applies for writing messages and drawing pictures with chalk on public sidewalks.

As with all censorship, the important legal question to ask with art is: Who's doing the censoring? The First Amendment prevents the government from restricting ("abridging") speech.

Just like other forms of speech and expression – including what public school students say, books in libraries, and songs on the radio – there are some narrow ways government can censor art under the First Amendment. For example, a public street art performance that uses full nudity and sex acts could be censored because narrowly drafted public nudity laws have been upheld even against First Amendment challenges.

A private art gallery or museum can censor, restrict, refuse to display, or may otherwise obscure an artist's work. That may run against the spirit of free speech, but it doesn't violate the First Amendment. In fact, these galleries and museums also have their own free speech rights in choosing what kind of art they want to display.

Discover 10 examples of art censorship from government, public backlash and private entities

1. Florida and Michelangelo's David (2023)

The first example of art censorship involves one of the most famous artistic works of all time. As a public charter school devoted to liberal arts education, the Tallahassee Classical School uses historical art in its classrooms. Hope Carrasquilla was the school's principal. During a lesson on Renaissance art, a teacher showed pictures of Michelangelo's David, which depicts the naked male body. Some parents complained that they weren't warned that their kids would see it. Carrasquilla resigned under threat of being fired. Many people voiced their support for her and the need for classical arts education. The museum in Florence that houses the real David statue flew Carrasquilla and her family to Italy to see it.

The head of the charter school's board told journalists that the principal being forced out wasn't solely related to the statue lesson. He also said the issue was that parents weren't notified in advance, telling Slate, "parents are entitled to know anytime their child is being taught a controversial topic and picture."

After public backlash, the Florida Department Education clarified state rules on arts education, saying in a statement, "The Statue of David has artistic and historical value. Florida encourages instruction on the classics and classical art, and would not prohibit its use in instruction."

2. U.S. Capitol and police painting (2017)

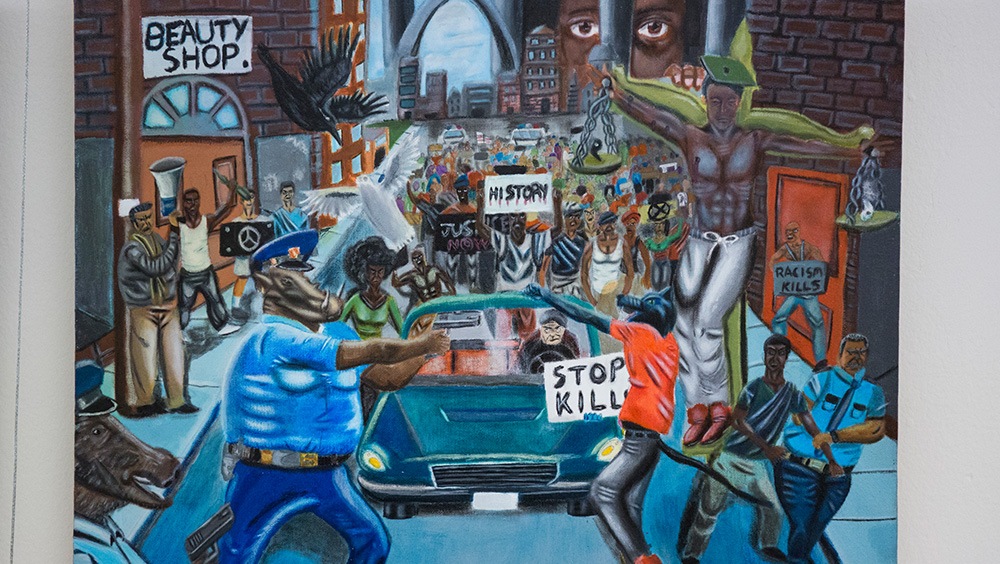

High school artist David Pulphus had his work displayed in the U.S. Capitol after winning a congressional competition. The painting, a commentary on social justice following the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Missouri, was criticized by police unions, media commentators and members of Congress as it depicted police as animals. The painting was removed. Pulphus and a member of Congress sued, saying the removal violated the First Amendment. A federal judge ruled it was OK to remove the painting, as Congress has a right to decide what art it wants to display in the Capitol without violating anyone's First Amendment rights.

A painting depicting Ferguson, Missouri, with the image of a pig in a police uniform aiming a gun at a protester.

3. Prophet Muhammad and Hamline University (2022)

Depictions of the Prophet Muhammad – artistic, cartoon and otherwise – are no stranger to controversy. Their use in education and in satirical magazines like France's Charlie Hebdo have sparked major world incidents given their sensitivity in the Islamic faith. Erika López Prater, a former professor at the private Hamline University in Minnesota, got a taste of that when she showed artistic depictions of the Prophet Muhammad in a lesson about Islamic art. At least one student said showing the images was offensive and complained to school officials. López Prater's adjunct contract wasn't renewed, and she later sued the university. The Council on American-Islamic Relations said in a statement that the former professor's actions were not bigoted or Islamophobic while expressing support for Muslim students "who argue that displaying depictions of Prophet in the classroom is harmful and also unnecessary."

4. China and Ai Weiwei (2011)

China doesn't have free speech protections like those in the First Amendment, so stories of art censorship there may not be surprising. Even so, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is widely known for his criticism of the government and clashes with its ruling Communist Party. In 2011, he was jailed for 81 days and put under house arrest for several years. Authorities destroyed his art studio, saying it was for a development project. They forced a Shanghai museum to remove his work from an exhibit. He moved to the U.S. in 2018 and continued his exhibits here – with First Amendment protections.

Workers put up a two-story-high black-and-white photograph of Ai Weiwei outside the Lisson Gallery in London in 2011.

5. University at Buffalo and segregation signs (2015)

Art can remind people of historic wrongs in an uncomfortable way. People at the public University at Buffalo in New York saw that first-hand when art student Ashley Powell used a project about Jim Crow segregation laws to place "White Only" and "Black Only" signs by drinking fountains and bathrooms on campus. It was meant as a reminder of the historical racism that still exists. Some students took offense. The university removed the signs and released a statement saying it would "review this matter through appropriate university policies and procedures." Powell explained the project following debate on campus, writing in the student newspaper, "This project, specifically, was a piece created to expose white privilege."

6. Rockefeller Center covers Sept. 11 sculpture (2002)

Not even a year had passed before a sculpture meant to commemorate the Sept. 11 terrorist attack was censored in New York City. Rockefeller Center, a private company, covered and later removed the bronze work of artist Eric Fischl following public criticism. The work called "Tumbling Woman" aimed to memorialize those who fell or jumped to their deaths from the World Trade Center. One person told a New York TV station, "It's not art. … It is very disrupting when you see it."

Press preview, on September 1, 2016 held for 'Rendering the Unthinkable: Artists Respond to 9/11', a major exhibition at the 9/11 Memorial Museum featuring artwork by 13 artists reacting to the terror attacks, including Eric Fischl's bronze statue 'Tumbling Woman.'

7. "The Holy Virgin Mary" (1999) and "Piss Christ" (1987)

As mayor of New York City in 1999 and a practicing Catholic, Rudy Giuliani didn't like the publicly funded Brooklyn Museum displaying artist Chris Ofili's painting "The Holy Virgin Mary." Giuliani called it "sick" and considered it sacrilegious with its use of elephant dung and bare butts cut from pornographic magazines. Giuliani threatened to cancel a larger exhibition at the museum if the piece wasn't removed. Going further, he cut off the museum's budget and said he'd make it vacate the building. The museum sued, and a federal judge ruled Giuliani violated the First Amendment. Ofili, who is Black and Catholic, called his painting "a hip-hop version" of the Virgin Mary. The piece returned to New York in 2018 after being donated to the Museum of Modern Art.

In a similar way, visual artist Andres Serrano has stirred intense debate over his 1987 photograph of a crucifix submerged in his own urine. The work called "Piss Christ" (also called "Immersion") has been torn down, censored, protested and called blasphemous for decades, including when it toured in New York in 2012. In 2015, The Associated Press removed the photo from its online archive after the high-profile terrorist attack against French satire magazine Charlie Hebdo over images of the Prophet Muhammed. In 2023, a California high school removed the image from a lesson in its international baccalaureate program after a student who was not in the class objected to possibly seeing it in the future, sparking outcry from parents about its use in a lesson about the question "what is art?" Serrano told The Guardian, "I'd say 'Piss Christ' is a reflection of my work, not only as an artist, but as a Christian. … So if 'Piss Christ' upsets you, maybe it's a good thing to think about what happened on the cross."

8. Congress, arts funding and the Supreme Court (1998)

After photographer Robert Mapplethorpe drew ire from members of Congress for provocative, sexually explicit photography funded through a federal National Endowment for the Arts grant, concerns grew about government funding controversial art. Congress passed a 1990 law that restricted criteria for awarding grants. The law allowed the NEA to weigh community standards in awarding money to artists and museums. Several artists sued to overturn the law, saying it violated the First Amendment. In a 1998 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the law and said the NEA doesn't need to fund art projects if they violate standards of "decency and respect." In other words, the bar is high to punish or censor art, but it's lower for government in deciding when to actively fund or support creating it.

Activists demonstrate in the streets of downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1990, as jury selection began in the obscenity charges against the Contemporary Arts Center for exhibiting photographs by late artist Robert Mapplethorpe.

9. Social media, art and nudity

Social media companies are not bound by the First Amendment. They have a free speech right to moderate content as they wish. Many social media platforms' policies prohibit pornography but allow nudity for educational, news or artistic purposes.

However, automatic filters and human moderators sometimes do censor art and photographs with important historical value.

For example, performance artist Marina Abramović is used to controversy in her 50-year career dealing with nudity – often her own. The Serbian-born artist has been called "the most dangerous woman in art." Social media companies like Instagram, owned by Meta, have censored posts about her work, with automatic filters flagging them for nudity.

Similarly, a Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnam War picture by photojournalist Nick Ut was removed from Facebook for violating its nudity policy (Facebook later reversed its ruling). Both artistic and news images raise questions about how processes meant to protect people from harmful content may unintentionally censor art.

10. Graffiti and sidewalk chalk in Seattle (2023) and Selah (2020)

Many cities and states have laws against graffiti and even sidewalk chalk in public spaces and private buildings. Broadly speaking, the laws do not violate the First Amendment because while speech is protected, property destruction and vandalism are not. However, challenges to such local laws have raised questions about how they're enforced and whether they violate the First Amendment.

In 2023, a federal judge stopped Seattle from enforcing its anti-graffiti law, calling it overly broad. The challenge came from people who were arrested after writing Black Lives Matter and anti-police messages with sidewalk chalk outside a police precinct. The judge said the city's law allowed police to arrest or cite people based on the content of the message and the officer's personal views, which violates the First Amendment. In their lawsuit, the plaintiffs showed images of police officers themselves writing messages with sidewalk chalk at pro-police community events.

In 2020, city officials in Selah, Washington, drew national attention for erasing chalked messages in streets and on sidewalks supporting Black Lives Matter following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The city erased the messages with water and threatened one family, who lived in a cul-de-sac, with prosecution for malicious mischief. Some legal experts believed the city's actions violated the First Amendment if officials selectively targeted the family and art based on the content of the message. After several instances of the city removing the messages from the street, neighbors began writing similar ones in their private driveways, where the city could not legally enforce its anti-graffiti law.

Pedestrians walk past graffiti on a building inside the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest zone in Seattle in 2020.

What's the bottom line on art censorship and the First Amendment?

The First Amendment broadly protects speech and expression, which includes art in the broadest sense. While private schools, private museums, and social media companies are not legally required to follow it, they can run against the spirit of free speech when censoring art.

Just like there are many forms of speech – including what you wear, write and sing – there are also many forms of art. The First Amendment broadly prevents the government from censoring art (with some exceptions). But it doesn't prevent an artist from getting harsh reviews or having their work boycotted, since anyone can use their own free speech to criticize.

Scott A. Leadingham is a Freedom Forum staff writer.

Teachers Face Limits on Their Election-Related Speech

National Security and the First Amendment: When Can Rights Be Limited?

Related Content