How Bob Dylan Embodied First Amendment Freedoms Through His Music

He’s won a Nobel Prize for literature, sang for presidents and a pope, joined the March on Washington for civil rights, and petitioned to free a man unjustly jailed for murder.

Singer-songwriter Bob Dylan has used his voice and the freedoms of speech, assembly and petition to call out racism, war and injustice for decades. Few musicians can match the impact his songs had on the 20th century and still do today. And the right to express ideas through music is a freedom brought to us by the First Amendment.

A 2024 Oscar-nominated movie starring Timothée Chalamet as Dylan tells the story of how “A Complete Unknown” from Minnesota arrived in New York City’s Greenwich Village in 1961 and captured the spirit of restless, angry young Americans through his music. The film also features a fictionalized version of artist and activist Suze Rotolo. Rotolo, Dylan’s girlfriend from 1961 to 1964, was a member of the Congress of Racial Equality and an anti-nuclear weapons group; she inspired some of Dylan’s themes of the era.

“I don’t write no protest songs,” Dylan said to introduce “Blowin’ in the Wind” at Gerde’s Folk City, a Greenwich Village club at the center of the folk music scene in 1962. The song nonetheless ranks No. 17 on Rolling Stone magazine’s 2025 list of the 100 Best Protest Songs of All Time.

The song became an anthem of the Civil Rights and anti-war movements as it asks, “And how many years can some people exist before they're allowed to be free?” Sam Cooke said the song inspired him to write his civil rights anthem “A Change is Gonna Come” one year later. At a 1997 concert in Bologna, Italy, Pope John Paul II said the wind Dylan referred to was the Holy Spirit.

Dylan said he wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind” in 10 minutes. Six decades later, the song, like much of his work that’s made possible by our First Amendment rights, is still relevant.

Dylan took inspiration from stories reported by the press

Dylan long had a challenging relationship with the press and music critics, who at times questioned his distinctive voice, ability to sing and his intentions. He looked to traditional and folk music for inspiration, but his songs reflected the issues of the times, such as the Vietnam War (“Masters of War,” No. 6 on the Rolling Stone list) and the rise of the Civil Rights Movement.

He sang of the 1955 torture and lynching of Emmett Till (“The Death of Emmett Till”), a Black teen visiting relatives in Mississippi, and of the 1963 death of a Black Baltimore hotel worker at the hands of a rich white tobacco farmer in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” — No. 26 on Rolling Stone’s list. The song tells the story of how the farmer, drunk and angry that his drink order was slow to arrive, struck Carroll with his cane. She died of a stroke. He was sentenced to six months — to be served after his tobacco crop was harvested.

He stood up to censorship

In 1963, Dylan was invited to sing on CBS’s star-making “The Ed Sullivan Show.” He planned to sing “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” a song that mocked the conservative John Birch Society and its efforts to root out communists in society. Sullivan cleared the song, but CBS lawyers feared a defamation lawsuit and asked him to alter the lyrics or sing another song. Dylan responded that that was the song he planned to sing, and he walked out. He never performed on the show.

As a private entity, CBS had the right to limit what Dylan sang, and Dylan had the right to refuse those limits.

He was no stranger to controversy

In December 1963, Dylan said he empathized with Lee Harvey Oswald, who assassinated President John F. Kennedy, as he accepted the Tom Paine Award from the National Emergency Civil Rights Committee, a group that celebrated the Bill of Rights. “I saw some of myself in him,” Dylan said, to boos and hisses from the crowd. He often said the same of other figures he sang about from controversial perspectives. Writing afterward to the committee, Dylan explained he was referring to the violence of the times.

At the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, Dylan stunned organizers and the folkie crowd by using electric instruments on his song “Like a Rolling Stone.” The crowd booed. At one show during his 1966 concert tour in England, a man screamed out that Dylan was a “Judas!” for moving from acoustic protest songs to electrified rock ‘n’ roll.

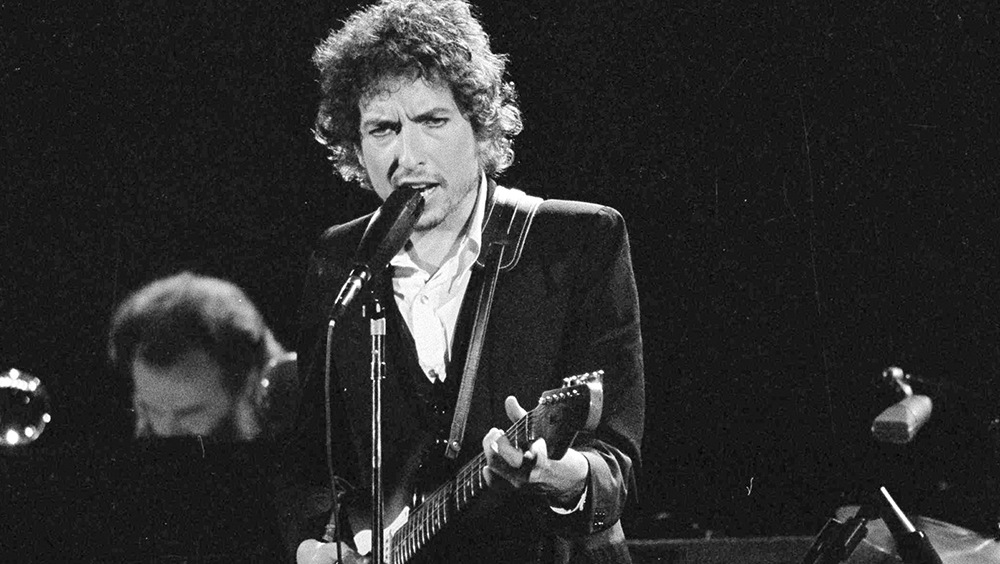

Bob Dylan performs in Los Angeles in 1974.

He supported civil rights through his music

As a quarter million people assembled for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, Dylan was among the musicians including Odetta, Mahalia Jackson and Joan Baez asked to sing to the crowd. Dylan sang of the death of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, shot dead in his driveway just weeks earlier in Mississippi. The song, “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” blames rich white politicians for turning poor white people against Black people.

Earlier that summer, Dylan traveled to Greenwood, Mississippi, to see Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee members working to register voters. There, too, he sang “Only a Pawn in Their Game” to a crowd of sharecroppers, with Ku Klux Klan members lurking in the background, weeks after Evers’ assassination.

He assembled with other artists to aid farmers and fight famine and apartheid

Dylan was among the 40-plus all-star musicians who sang on the 1985 hit “We Are the World” to benefit people starving from a famine in Ethiopia, part of the Live Aid movement.

At the Live Aid concert in Philadelphia, Dylan said from the stage that he hoped American family farmers, facing bankruptcy amid plunging land values, could get some of the money. That comment inspired Willie Nelson, and six weeks later, Nelson, Neil Young and John Mellencamp launched Farm Aid with a concert and a nonprofit that continues to support family farmers today.

His song petitioned to free boxer Hurricane Carter

In 1975, Dylan went to prison to visit boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, who was convicted of fatally shooting three people in a bar in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1966. Two witnesses had just recanted their testimony, saying they had been pressured to identify Carter and another defendant. The song Dylan wrote following his visit, “Hurricane,” became a top 40 hit and drew attention to the cause. He headlined fundraising concerts for Carter in New York and Houston in 1976. But later that year, Carter and his co-accused, John Artis, were convicted again when one of two witnesses who recanted earlier testimony changed his testimony again. In 1985, a federal judge overturned the convictions, saying prosecutors had “fatally infected the trial” by withholding evidence. Carter was freed, and in 1988, the charges were dismissed.

A parody portrait of Dylan and a First Amendment battle

Artist Chuck Close painted a parody version of a nude Dylan – the artwork was dubbed “Big Bob” – that was part of an exhibit at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 1967. The provocative content spurred the university to remove the exhibit, and Close sued, saying the art was protected on First Amendment grounds. He won initially but lost on appeal.

RELATED: Parody, satire and the First Amendment

A songwriter who challenged his country

In 2012, President Barack Obama awarded Dylan the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest honor for civilians. Dylan was the first musician to be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 2016 – but true to idiosyncratic form, he skipped the official ceremony, opting for a private speech instead. He accepted the Grammys’ MusiCares Person of the Year Award in 2015 and in his speech, both praised and poked fun at fellow musicians and took on critics who derided his voice and his songs.

Now in his 80s, Dylan continues to tour, his songs still prodding and provoking the nation. As he sings in the closing lines of “The Death of Emmett Till,” “If all of us folks that thinks alike, if we gave all we could give, we could make this great land of ours a better place to live.”

Why New Utah Social Media Laws Are Unconstitutional

Related Content