What Is Book Banning and Is It Unconstitutional? The Complete Guide

You have probably heard about “book banning” but may wonder exactly what it is. You’re not alone. Even those who feel strongly about the issue and experts on the topic have different views about when a book has been banned from a school or library.

In this post, we take a deep dive into book bans and the First Amendment. We answer commonly asked questions, such as "What is book banning?" and "Is book banning unconstitutional?" We also take a look at how the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled on cases related to book bans and how data shows that it's a phenomenon on the rise.

What is book banning?

To some, a book has only been “banned” when it is completely inaccessible because it has been removed from a public-school curriculum, public school library or public library. To others, any government action that makes it harder to read the book – such as requiring parental permission to read the book – qualifies as a ban.

School and library boards tend to immediately restrict access to a book as soon as it is challenged rather than letting a full review process play out. It is important to remember that someone “challenging” a book is not the same as “banning” the book. In fact, that person is exercising their First Amendment rights of free speech and petition by requesting government action.

Disagreement continues about when the removal of a book violates the First Amendment and when it does not because the one U.S. Supreme Court ruling on book access in schools was highly divided and has sometimes been applied in conflicting ways.

Is book banning unconstitutional?

Yes, book banning can violate the First Amendment rights of students and others who have a right to receive information and ideas contained in those books. Book banning violates the First Amendment when public school or other government officials ban books from a library because they dislike the ideas contained in those books or disagree with the viewpoints conveyed in the books.

When public school officials remove a book from a public school library because they don’t like the ideas or political perspectives in the book, they have committed viewpoint discrimination under the First Amendment. Viewpoint discrimination means that government officials have targeted private speech for special unfavorable treatment based on its message. When government officials engage in viewpoint discrimination, they violate the First Amendment.

RELATED: 15 of the most famous banned books in U.S. history

However, library officials can remove a book if it is “pervasively vulgar” or “educationally unsuitable.”

Most book banning controversies arise in the context of public schools. Some advocacy groups contend that certain books are too frank or candid in discussing topics such as LGBTQ+ themes, sexuality, violence, drug use or witchcraft. Books with topics such as race, gender and sexual orientation are often argued to be “too advanced” for school-aged children – and therefore inappropriate for a school curriculum or library – no matter how the topic is presented.

The U.S. Supreme Court addresses book banning in famous case

The U.S. Supreme Court addressed the banning of books in a public school library in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico (1982).

In 1975, the school board determined that nine books should be removed from a local high school and junior high school. The nine books were:

- “Slaughterhouse-Five” by Kurt Vonnegut

- “The Naked Ape” by Desmond Morris

- “Down These Mean Streets” by Piri Thomas

- “The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers” edited by Langston Hughes

- “Go Ask Alice” by Anonymous

- “Laughing Boy” by Oliver La Farge

- “Black Boy” by Richard Wright

- “A Hero Ain’t Nothing but a Sandwich” by Alice Childress

- “Soul on Ice” by Eldridge Cleaver

Six of the books were created by Black authors: Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Alice Childress, Desmond Morris, Eldridge Cleaver and Piri Thomas. The school board appointed a book-review committee, which recommended that only two of the books (“The Naked Ape” and “Down These Mean Streets”) be removed. However, the school board rejected the committee’s recommendations. The board found some of the books “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy.”

RELATED: Is obscenity protected by the First Amendment?

Four high school students and one junior high school student sued in federal court, contending their First Amendment rights were violated. A federal trial court rejected their claim; however, a federal appeals court reinstated it. The school board then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In his plurality (less than a majority) opinion for the court, Justice William Brennan explained that “local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.”

The fact that this was a plurality decision has proven problematic. Former Freedom Forum Fellow Tony Mauro wrote of the Pico case: “Even though Supreme Court precedents usually last for a long time, Brennan’s forceful 1982 pronouncement opposing the removal of books from school libraries has mostly been ignored,” quoting First Amendment expert Eugene Volokh’s theory that the plurality decision is the reason.

The line drawn in Pico allows decision makers to remove books that are not educationally appropriate but says they cannot remove books because they disagree with the viewpoint they contain. This standard has often been applied in a way that confuses the two.

Still, Brennan’s opinion contains several nuggets for First Amendment advocates. He emphasized that restricting student access to books infringes on their right to receive information and ideas. He also explained that under the First Amendment, you cannot silence ideas contained in books simply because you don’t like them.

Brennan did acknowledge that school officials could remove books if they were “pervasively vulgar” or “educationally unsuitable.” However, disagreement with the viewpoints expressed in a book is not an acceptable or constitutional reason for removing books under the First Amendment. This means that book review committees must ensure that they are focusing on whether the materials are suitable for specific age groups, not whether they agree or disagree with the ideas or viewpoints in the books.

Attorney Arthur Eisenberg, who was one of the lawyers for the students, told me in an interview for my book for Freedom Forum, “The Silencing of Student Voices,” that “The Pico case is significant because it resisted the oversimplified claim advanced by the school board that because the school board buys the books, they have the authority to determine what books are on the library shelves without any First Amendment concerns.”

The Pico decision remains important because it reiterates the First Amendment right to receive information and ideas. It also is important because book banning or book removal controversies are occurring at a significant rate.

Book banning is a phenomenon on the rise

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom reports that during 2023, there were challenges to 4,240 individual book titles.

Likewise, PEN America reports that attempts to ban books have increased in recent years.

PEN’s report “Banned in the USA: The Mounting Pressure to Censor” cites “3,362 instances of book bans in U.S. public school classrooms and libraries” from July 2022 to June 2023.

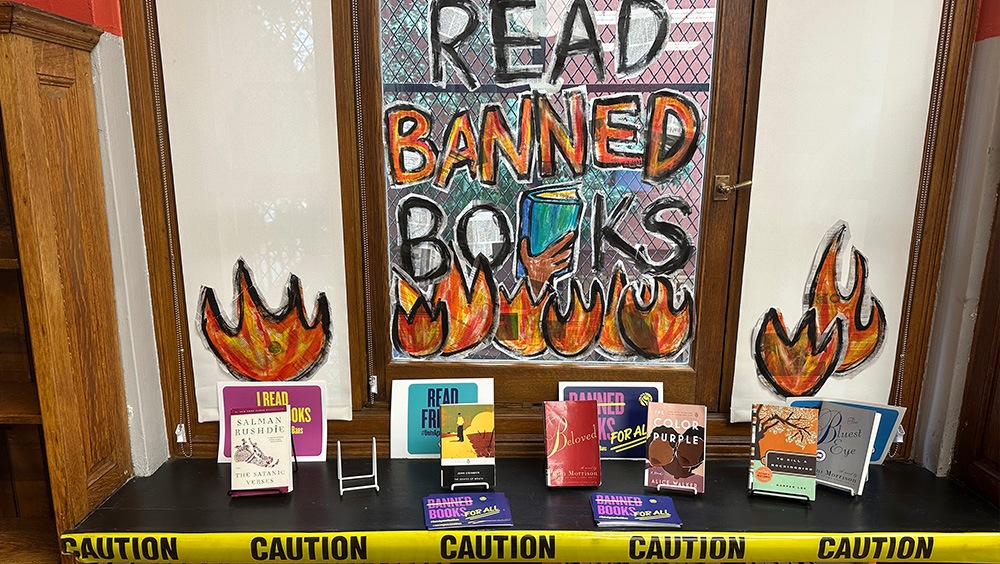

A librarian arranges a display of banned books during Banned Books Week at a New York Public Library branch in 2022.

PEN America is one of several plaintiffs who filed a lawsuit challenging the removal of numerous books from several public schools in Escambia County, Florida. The lawsuit claims that there is a concerted and consistent effort to remove books from public school libraries in the school district because school officials don’t like the political or ideological themes in the books.

The push to ban books occurs with enough frequency to alarm First Amendment advocates, educators and others who worry about denying kids access to information. Often, it is parents of school children who file complaints about books, contending that they are inappropriate for their kids in schools. Parents have a First Amendment right to petition government officials. However, some of the parental complaints lead to unfair targeting of books.

Books that discuss racism

In recent years, some states have passed laws that regulate what students can learn about the nation’s history on race, impacting access to books.

For example, a branch of a group called Moms for Liberty in Williamson County, Tennessee, complained that the book “Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My Story” by Ruby Bridges teaches anti-American values and must be banned by the new law.

Bridges’ book tells the story of a young Black girl in New Orleans who integrated an all-white elementary school. The book teaches about injustice in American history.

Books with LGBTQ+ themes

According to the American Library Association, more than 2,500 books were challenged in public libraries in 2021 and 2022. Of these, almost half were written by or about LGBTQ+ people. A study by PEN America of book challenges in schools during the 2021-2022 academic year reveals a similar level of targeting books with LGBTQ+ themes or characters.

A Washington Post study of challenges catalogued during that school year found that individual books had been challenged on the following grounds:

- “The theme or purpose of this book is to confuse our children and get them to question whether they are a boy or a girl,” a North Carolina challenger wrote of “Call Me Max,” which centers on a transgender boy.

- A Texas challenger wrote that “King and the Dragonflies,” which tells the story of a 12-year-old Black boy in Louisiana grappling with his attraction to men, will give “ideas to children [on how to] discover that they are gay [and] how to persuade others they may be gay as well.”

- And in Georgia, a challenger wrote of “The Poet X,” which features a same-sex couple, “Books like this is where teens get the idea it’s ok!”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a First Amendment fellow with the Freedom Forum.