20 of the Most Famous Protests In U.S. History

Two First Amendment freedoms are the least known: freedom of assembly and freedom to petition. Freedom of assembly protects the right to gather peacefully. Freedom to petition protects the right to tell government officials without fear of punishment if you think a policy is good or want something to change.

When people have a protest, march or rally, they use freedom of assembly. They may also use freedom to petition.

Throughout U.S. history, famous protests have shaped government policies, public opinion and future protest movements.

Famous protests have also raised questions about when these freedoms may be limited to protect public order and safety.

Discover 20 of the most famous protests throughout U.S. history

These famous protests include some of the earliest, largest and longest running. They show a diverse range of causes, and they cross time and place. Many tested the limits of the First Amendment. Some helped expand these freedoms. Some went beyond protected protest into illegal actions.

Editor's note: Protests listed in chronological order.

Boston Tea Party | Dec. 16, 1773

The Boston Tea Party is one of the most famous protests of colonial times.

In Massachusetts in 1773, American colonists were upset about British tax policies, particularly on tea. On Dec. 16, a group of colonists put on paint, feathers and blankets to look like Indigenous people. They went to the harbor and dumped tea from a British ship into the water.

But England did not change the tax policies. Instead, it closed the harbor.

The First Amendment did not exist yet. If it had, destroying someone else’s tea would not have been a protected way to protest.

Later, the nation’s founders put the right to petition into the First Amendment. They wanted to be sure people had an outlet to share their views.

Illustration of the Boston Tea Party.

Coxey’s Army | March-July 1894

In 1894, the United States was in a depression. Activists Jacob Coxey and Carl Browne wanted the government to provide jobs for the unemployed. They led a group to Washington, D.C., to ask for help. The group became known as Coxey’s Army.

Politicians and the media described Coxey’s Army as tramps and vagrants. They were considered dangerous. Camped near the city, they tried to hold protests for nearly two months.

Since 1882, speeches and protests at the U.S. Capitol were illegal. Coxey was arrested for walking on the grass and having a “banner,” which was just a pin on his jacket. He was also stopped from giving a speech at the Capitol building.

Soon it became clear that no policy would change. The protesters were forced to leave when the Virginia militia burned their camp down.

Some politicians feared that such protests would become an American habit. They were right.

Fifty years after this first march on Washington became a famous protest, Coxey was invited to the Capitol to finish his speech.

Coxey's Army parades in Washington, D.C. on bikes, in wagons and on foot.

Women’s Suffrage Parade | March 3, 1913

In 1913, women could vote in nine states. But activists wanted all women to be able to vote. Suffragist Alice Paul thought a march in Washington could get attention for the cause. Organizers chose March 3, the day before new President Woodrow Wilson would be sworn in.

The women planning the event wanted to be sure they had permission for what was planned to be a calm, formal procession. At the time, city officials sometimes allowed marches or parades only for groups the officials found respectable. While this treatment was common, the First Amendment actually protects assembly no matter the cause.

On the day of the march, the police and military could not control the crowd. People watching disrupted the march, injuring some marchers. Later, Congress blamed police for not protecting the marchers. The police chief resigned.

The women who marched went on to use more disruptive kinds of protests. Six years later in 1919, the 19th Amendment gave all women the right to vote.

Women marching in a suffrage parade before the passing of the 19th Amendment.

Bonus March | May-June 1932

After World War I ended in 1918, veterans were promised bonuses that would be paid in 1945. But when the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, many veterans needed the money sooner.

In May 1932, Walter Waters of Portland, Ore., led a group to Washington, D.C., to ask for their money. The “Bonus Army” camped near the U.S. Capitol for nearly three months. Crowd estimates vary, but it’s likely that 10,000 to 25,000 veterans participated.

At the time, protests at the Capitol were technically illegal. But they were common and were often allowed. The Bonus Army even got help from the D.C. police chief.

Congress was divided on providing the bonus. The House of Representatives passed legislation to provide it, but the bill failed to pass in the Senate. Ultimately, Congress did not give the veterans their bonus money early.

Meanwhile, concerns grew about the camp. So did fears that Communists were part of the group. At the time, First Amendment rights could be limited if there was “clear and present danger” of harm to public safety or national security. Today, it is much harder to limit these rights.

President Herbert Hoover ordered police and the army to get rid of the protestors. The camps were teargassed and burned, shocking many at the treatment of the veterans.

A federal soldier passes by burning shacks that fleeing Bonus March veterans abandoned.

Civil Rights Movement Marches in Alabama | 1963-1965

During the Civil Rights Movement, people used many types of protest to seek equal rights for Black Americans.

In May 1963, Black schoolchildren in Birmingham, Ala., left their classrooms to march for civil rights in The Children’s Crusade. They were attacked by police. News of the attacks on children angered people across the country. President John F. Kennedy spoke up for civil rights. The crusade eventually contributed to the end of segregation in Birmingham businesses.

In March 1965, activists planned a march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The governor said the march would not be permitted. Police at the Edmund Pettus Bridge beat the marchers. After footage went on TV, President Lyndon B. Johnson promised a voting rights bill. Two weeks later, protesters tried the march again. This time they had federal protection. A national voting rights act became law that August.

Martin Luther King Jr. and civil rights marchers head for Montgomery, Alabama on March 21, 1965.

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | Aug. 28, 1963

Among the most famous protests in U.S. history is the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Organizers described this event as a “living petition.” The day is perhaps most remembered for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

A broad group of organizations came together to organize the 1963 march, and they worked closely with the federal government.

The group wanted all its activity to be within First Amendment protection. That meant acting within their permits and using no violence.

On the day of the event, record-breaking numbers of people came to march. Unlike past protests, many people stayed home because they could watch it on TV.

A small group of people protested the march. Two were arrested, but mostly, the day went smoothly.

Organizers also met with leaders in Congress and the president. The main goal, though, was to show the public how many people supported racial equality.

Large crowds gather on the National Mall during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

March on the Pentagon | Oct. 21, 1967

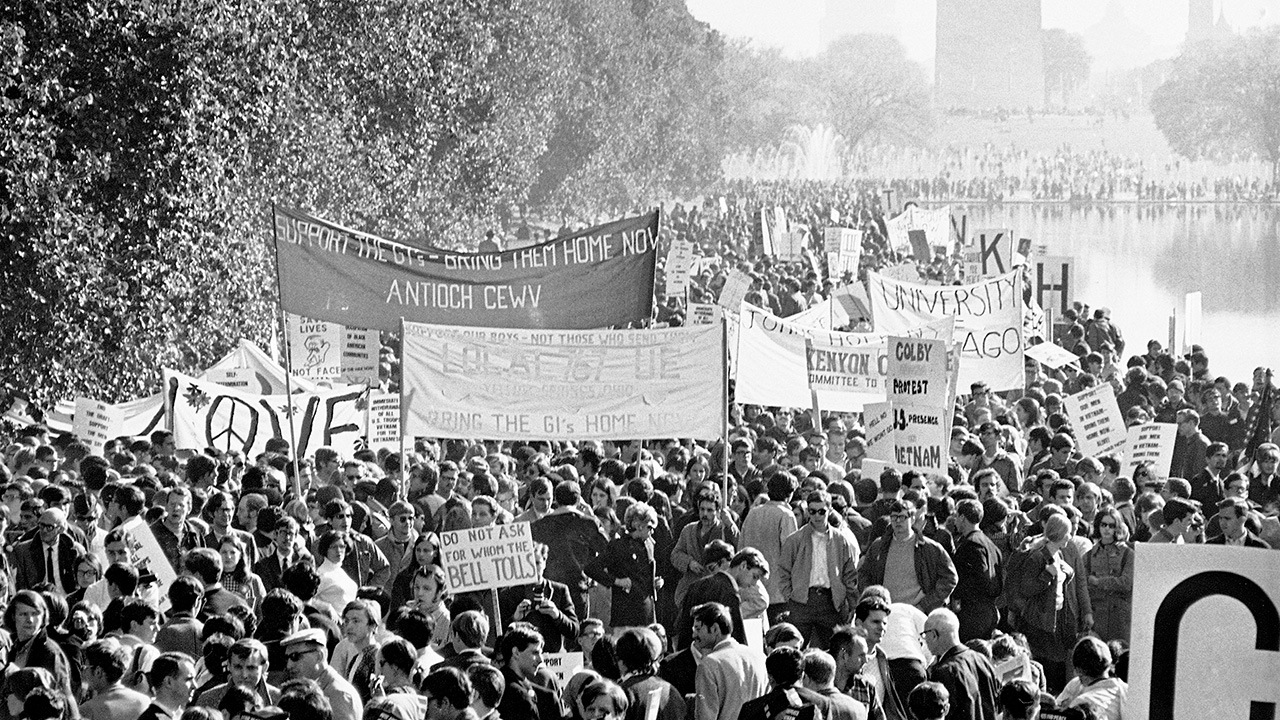

In 1967, opposition to the Vietnam War was growing, especially among the counterculture movement. The National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam organized a protest march from the Lincoln Memorial to the Pentagon.

On the day of the march, music groups like Peter, Paul and Mary performed at the Lincoln Memorial. As the crowd marched toward the Pentagon, police partially blocked the route. Protestors sat until the march could continue.

At the Pentagon, the military had installed fences to keep protesters out. Armed soldiers were waiting.

Some protestors put flowers in the barrels of soldiers’ guns, creating iconic images of “flower power.”

The protest was mostly peaceful. Between 650 and 1,000 protesters were arrested for going through broken fences and trying to enter the building. Those actions were trespassing, which is not protected by the First Amendment.

The protests were finally broken up with tear gas. Popular opinion against the war continued to grow.

Anti-war protestors gather opposite the Lincoln Memorial during the March on the Pentagon.

Stonewall Uprising | June 28-July 3, 1969

Today, the First Amendment protects gathering and expression for LGBTQ+ people just like everyone else. But in the 1960s, there were laws that made it hard for gay people to gather.

The Stonewall Inn in New York City served gay customers. One early morning in June 1969, the police raided the bar. People at the club fought back. A six-day uprising followed with violent clashes with the police. Meanwhile, people distributed pamphlets in support of gay rights.

The uprising helped spur a broad gay rights movement. Within a year, New York had three gay newspapers.

In 2016, the Stonewall Inn became a historic landmark. Today, the Stonewall uprising is remembered through parades and marches throughout Pride month in June.

Two police officers have an altercation with two men after a Gay Power march in New York City on Aug. 31, 1970.

Kent State Shootings | May 4, 1970

Four students at Kent State University died and nine were hurt when they were shot by Ohio National Guard members during a protest of the Vietnam War. The incident shocked people and showed divisions over the war. A photograph of the aftermath won the 1971 Pulitzer Prize.

The war was unpopular, but U.S. involvement had grown. There was a nationwide student strike. Disturbances at Kent State starting on May 1 led the National Guard to be called in.

On the evening of May 2, an officer training program building was burned down. Tensions grew.

On May 4, a crowd gathered to protest the war and the National Guard presence.

Authorities ordered the crowd to leave. Some students yelled and threw rocks.

Guard members began firing into the air, ground and crowd; the reason why remains disputed. Four students died: One was shot in the back; one was on her way to class. Of the nine students hurt, one was paralyzed.

Kent State faculty marshals quickly moved in to prevent more violence. Classes did not resume for months. Students across the country protested in response.

A court later said orders to ban the rally were legal. During investigations, Guard members said they fired in self-defense because students were coming toward them threateningly. One federal case against eight guard members was dismissed. Another case was settled out of court.

Ohio National Guard soldiers walk toward war protesters at Kent State University.

March for Life | January 1973 – Ongoing

In January 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade that a Texas law banning most abortion violated a constitutional right to privacy. The landmark ruling made abortion legal nationwide.

Catholic lawyer Nellie Gray was among the religious leaders who protested the decision. She organized the March for Life a year later in Washington, D.C.

This famous protest has been an annual event for more than 50 years. It includes people who oppose abortion from a broad range of faith traditions and none. Many participants have also petitioned for change and supported candidates who share their views.

The event sometimes generated counter protests from supporters of abortion access. Thanks to the First Amendment, people of all views can assemble to share their messages.

In 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. It said states could have laws to limit more abortions. The March for Life continues and now advocates for such laws.

In 2023, a group of students from South Carolina who came to Washington, D.C., for the march were asked to remove clothing with march slogans or be required to leave the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, a public museum. Because such speech is protected from government interference, the students sued. The museum agreed not to punish such speech in the future.

Crowd of people gathered outside the Minnesota Capitol building protesting the U.S. Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade decision on Jan. 22, 1973.

National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights | Oct. 14, 1979

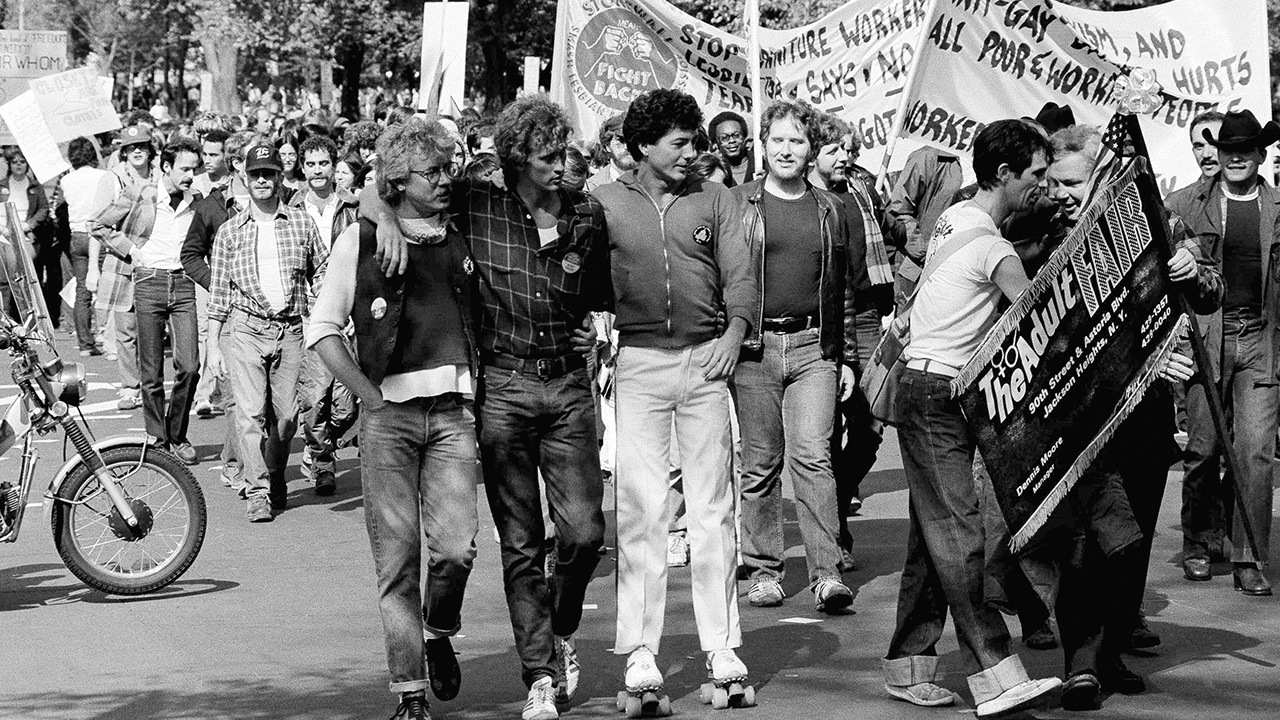

In the 1970s, the grassroots movement for gay rights was growing.

Gay activist and San Francisco Board of Supervisors member Harvey Milk was among those trying to unite the movement nationally. He was planning a march in Washington, D.C. when he was assassinated along with Mayor George Moscone in 1978.

After fellow supervisor Dan White was convicted of manslaughter instead of murder for the assassinations, protests of the verdict grew into the “White Night” riots.

Organizers set the Washington march for the next year. 1979 was the tenth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, which had spurred the movement.

The event included speakers such as poet Allen Ginsberg (who also participated in the 1967 March on the Pentagon) and Marion Barry, then-mayor of Washington, D.C. Participants also met with many members of Congress to petition them for gay rights laws.

Participants in a march sponsored by the National Gay Task Force assemble in Washington, D.C.

White House Peace Vigil | June 3, 1981 – Present

In June 1981, activist William Thomas started a vigil in the park in front of the White House to protest nuclear weapons. The vigil has been going on almost continuously since then.

Early in the protest, Thomas and his wife were arrested several times for camping in the park.

Later, activist Concepción Picciotto took over the vigil with help from volunteers. Over time, its messages have grown to include human rights and other causes.

The United States Park Police who oversee the area say that the protest does not require a permit as long as it is continuously occupied by a protestor who is not sleeping.

On two occasions in September and October 2013, the vigil’s tent and signs were briefly removed by park police. An overnight volunteer had left the property unattended. Both times, the belongings were returned the next day.

According to local publication The Georgetown Voice, “While the modest White House Peace Vigil does not command the enormous crowds or participation numbers in the way other large-scale D.C. protests tend to, it reflects a more intimate community of care, activist stamina, and a love for humanity.”

Concepción Picciotto sits in the snow on Feb. 10, 2010 as she continues her 24-hour-a-day peace vigil.

Tea Party Tax Day Protests | April 15, 2009

The Tea Party movement began in February 2009. Members protested tax policies and government spending. It was named after the Boston Tea Party.

On Tax Day, April 15, the group held protests across the country. One protest was in front of the White House. Police broke this protest up after someone threw tea over the White House fence.

The Tea Party movement has gone on to shape the modern Republican party and conservative populist movement.

Group of protesters in Arkansas hold signs and flags for the Tea Party Tax Day protest.

Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear | Oct. 30, 2010

Not all famous protests have a serious cause. Comedians Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart held a spoof of a political rally in October 2010.

The event poked fun at dramatic coverage of politics. It was an attempt to address the divisiveness that had come to define the era's politics.

Participants carried nonsense signs.

The event claimed to show the voice of the middle, while some found it to be left leaning.

Thousands gather for Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert's Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear on the National Mall.

Occupy Wall Street | Sept. 17 – Nov. 15, 2011

The slogan of Occupy Wall Street was “We are the 99%.” The movement protested income inequality and was inspired in part by the Arab Spring uprisings in the Middle East. Spurred by a blog post criticizing consumerism, it quickly grew into a global movement. It was supported by celebrities and the hacking group Anonymous.

The group began a sit-in at Zuccotti Park, a privately owned outdoor space in New York City. Law enforcement could not shut down the protest because it was on private property and was allowed by the owners. The camp was closed for health reasons nearly two months later.

Occupy did not have specific demands and was organized without leaders. It did have its own publications and a shared library at the camp.

The group also had marches. During one march on Oct. 1, more than 700 protesters were arrested for blocking traffic while marching across the Brooklyn Bridge. A judge later ruled that they should not have been arrested because police did not give them enough warning to move from the road.

Occupy has since grown into movements to end student loan debt and raise the minimum wage.

Protesters with Occupy Wall Street lead a march through Lower Manhattan.

Dakota Access Pipeline Protests | April 2016 – February 2017

In January 2016, the government approved the Dakota Access Pipeline. It would carry oil across land sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux. It could also poison their water.

The Sioux Nation sued. It also began a sit-in by a group of water protectors. People of many faiths gathered to pray and protest the pipeline.

Protestors pointed out that the Sioux Nation’s treaties with the U.S. meant they were on their own land. But the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers claimed it was now government land. That made the protests illegal.

Private security guards clashed with protestors near the construction site in September 2016. Law enforcement also responded. Eventually, they used water cannons and tear gas to break up the protest.

The pipeline was approved and became operational in June 2017.

Actresses Shailene Woodley and Susan Sarandon and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe member Bobbi Jean Three Lakes participate in a protest outside the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C.

Women’s March | Jan. 21, 2017

On Jan. 21, 2017, hundreds of thousands gathered in Washington, D.C., for the Women’s March on Washington. It was a protest against the rhetoric of the 2016 presidential campaign.

Similar protests were held around the country.

The protestors had many messages. However, like the women’s suffrage movement in the 20th century, it was criticized for not always including people of diverse backgrounds and perspectives.

A large crowd fills Independence Avenue during the Women's March on Washington.

March for Our Lives | March 24, 2018

The survivors of the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida organized a nationwide protest against gun violence.

The students lost 14 classmates and three faculty members in the Valentine’s Day shooting. The teens organized the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C., just six weeks later.

They spread the word on social media. Singers Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez offered support.

More than one million people participated across the nation.

Many of the student organizers were not old enough to vote, yet they still used their First Amendment freedoms to speak up against gun violence.

A large crowd fills Pennsylvania Avenue during the March for Our Lives protest.

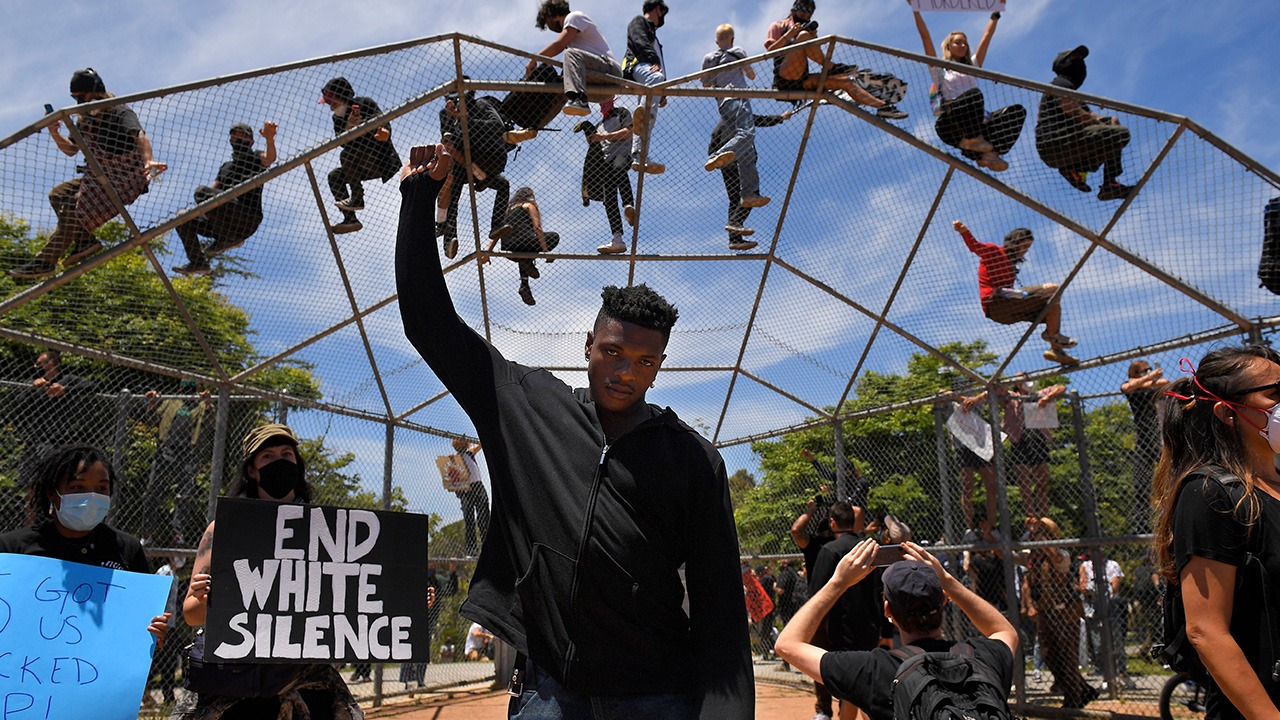

2020 Racial Justice Protests | May – August 2020

A series of deaths of Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement spurred a new public protest movement. On May 25, George Floyd was killed by law enforcement officers in Minneapolis. His death was captured on cellphone video and shared on social media. Eventually, protests spread from Minneapolis to more than 200 cities around the world.

At the time, many cities also had COVID-19 restrictions. Limits on gathering increased tension. In Washington, D.C., and other cities, people questioned the official responses to protests. Protestors were arrested or tear gassed. Some protests escalated to violence. Some cities enforced curfews.

Large and diverse groups gathered throughout the summer including on Juneteenth. A march on Washington on Aug. 28 reflected the 1963 civil rights protest.

Musical artist Jeleel stands with his fist raised in protest over the death of George Floyd.

U.S. Capitol Riot | Jan. 6, 2021

As Congress met to confirm the election of Joe Biden as president, protestors gathered.

Supporters of former President Donald J. Trump claimed election fraud had cost him victory. After Trump spoke to the crowd, they began marching to the Capitol.

The National Park Service had issued a permit for up to 30,000 people to protest the election results on the National Mall. According to data journalist Stephen Doig, estimating the actual size of the crowd with any accuracy is difficult.

The Capitol building grounds were closed for security. The First Amendment right to assembly can sometimes be limited like this for safety and security reasons, as long as all groups are treated the same.

During the protest, some people in the crowd pushed past barriers. Some broke into the Capitol. Some attacked guards. These protestors were no longer protected by the First Amendment. Assault and trespassing are not protected protest.

Many participants and guards were injured. One participant was killed by police. According to a Senate report at least seven people died because of the event.

The event sparked investigations in Congress. More than 1,000 participants have been arrested and more than 400 convicted.

A large crowd protests and riots at the U.S. Capitol.

Watch: Young People Wield the First Amendment for Civic Engagement

How A Famed Author Of Children’s Literature Is Facing The Book Banning Trend

Related Content