Religious Freedom FAQ

What does religious freedom mean?

Religious freedom means the right to believe and live by one's religious tradition — or lack thereof — and allows all citizens to shape their lives, whether private or public, based on personal and communal beliefs. Sometimes called the right of conscience, it protects all from action by government to control our thoughtful independence and prohibits the government from supporting any one faith or personal belief over others.

Why is religious freedom important to our society?

- Protecting freedom of conscience and the right to act upon one’s religious tradition — or lack thereof — is to respect and uphold the right of individuals to think and act as free citizens.

- Navigating a religiously diverse society also allows us to address the critical question "How do we live with each other’s deepest differences?”

Religious liberty is founded on the inviolable dignity of every person. To safeguard the right to act upon one’s is to respect and uphold the right of individuals to think and act as free citizens. Religious freedom is not based on social usefulness and is not dependent on the shifting moods of majorities and governments. A just society requires us to be respectful of this right, even for its smallest minorities and least popular communities.

Navigating a religiously diverse society also allows us to address the critical question "How do we live with each other’s deepest differences?” How do religious convictions and political freedom complement rather than threaten each other on a small planet in a pluralistic age? In a world in which bigotry, fanaticism, terrorism and the state control of religion are all too common responses to these questions, sustaining the justice and liberty of the American arrangement is an urgent moral task. Our ideal of religious freedom demands that we engage in these crucial questions, thereby strengthening our democracy for everyone. *

*Adapted from the Williamsburg Charter Summary of Principles.

Is the United States a Christian nation?

- No, the United States is not a formally Christian nation.

The establishment clause of the First Amendment prohibits government endorsement of any one religious tradition or religion over nonreligion. While many of the founding fathers were Christian and certainly held personal religious views, the Constitution was intentionally designed to separate church and state. The First Amendment upholds the ideal that no religion should be codified into law or imposed onto others.

Christianity — especially Protestantism — remains a dominant presence in American culture today, but this does not mean we live in a Christian country. Despite the demographic and cultural dominance of Protestantism in the United States, the First Amendment offers equal protection to religious minorities, including the religiously unaffiliated.

More: “Are We A Christian Nation?”

The First Amendment says nothing about “separation of church and state.” Where did this idea come from? Is it really part of the law?

- Although the words “separation of church and state” do not appear in the First Amendment, the establishment clause was intended to separate church from state.

- The establishment clause prohibits the government from favoring one religious view over another or favoring religion over nonreligion.

- The phrase “separation of church and state” originated from Thomas Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptist Association.

Although the words “separation of church and state” do not appear in the First Amendment, the establishment clause was intended to separate church from state. When the First Amendment was adopted in 1791, the establishment clause applied only to the federal government. That meant the federal government could not favor one religion over another, or belief over nonbelief. By 1833, all states had separated religion from government, providing protections for religious liberty in state constitutions. In the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court applied the establishment clause to the states through the 14th Amendment. Today, the establishment clause prohibits all levels of government from either advancing or inhibiting religion.

The establishment clause separates church from state, but not religion from politics or public life. Individual citizens are free to bring their religious convictions into the public arena. But the government is prohibited from favoring one religious view over another or even favoring religion over nonreligion.

Our nation’s founders disagreed about the exact meaning of “no establishment” under the First Amendment; the argument continues to this day. But there was and is widespread agreement that preventing government from interfering with religion is an essential principle of religious liberty. All the Framers understood that “no establishment” meant no national church and no government involvement in religion. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison believed that without separating church from state, there could be no real religious freedom.

The first use of the “wall of separation” metaphor was by Roger Williams, who founded Rhode Island in 1635. He said an authentic Christian church would be possible only if there was “a wall or hedge of separation” between the “wilderness of the world” and “the garden of the church.” Any government involvement in the church, he believed, corrupts the church.

Then in 1802, Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, wrote: “I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church and State.”

The Supreme Court has cited Jefferson’s letter in key cases, beginning with a polygamy case in the 19th century. In the 1947 case Everson v. Board of Education, the Court cited a direct link between Jefferson’s “wall of separation” concept and the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

What does “free exercise” of religion mean under the First Amendment?

- Free exercise of religion is the ability to both believe and act according to one’s religious tradition, or lack thereof.

- While the First Amendment protects religious freedom, the government may limit free exercise of religion when there is a compelling interest, such as public health or safety.

- The boundaries of limitation and what constitutes a “compelling interest” continue to change, and often differs from state to state.

The First Amendment states that the government “shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise of religion.” Those words are commonly called the “free exercise clause” of the amendment. Although the text sounds absolute, “no law” does not always mean “no law.” The Supreme Court has had to place some limits on the freedom to practice religion. To take an easy example cited by the Court in one of its landmark “free-exercise” cases (Reynolds v. U.S., 1878), the First Amendment would not protect the practice of human sacrifice even if some religion required it. In other words, while the freedom to believe is absolute, the freedom to act on those beliefs is not.

But where may government draw the line on the practice of religion? The courts have struggled with the answer to that question for much of our history. Over time, the Supreme Court developed a test to help judges determine the limits of free exercise. First fully articulated in the 1963 case of Sherbert v. Verner, this test is sometimes referred to as the Sherbert or “compelling interest” test. The test has four parts: two that apply to any person who claims that his freedom of religion has been violated, and two that apply to the government agency accused of violating those rights.

For the individual, the court must determine

1) Whether the person has a claim involving a sincere religious belief, and 2) whether the government action places a substantial burden on the person’s ability to act on that belief.

If these two elements are established, then the government must prove

1) That it is acting in furtherance of a “compelling state interest,” and 2) that it has pursued that interest in the manner least restrictive, or least burdensome, to religion.

The Supreme Court, however, curtailed the application of the Sherbert test in the 1990 case of Employment Division v. Smith. In that case, the Court held that a burden on free exercise no longer had to be justified by a compelling state interest if the burden was an unintended result of laws that are generally applicable.

After Smith, only laws (or government actions) that (1) were intended to prohibit the free exercise of religion, or (2) violated other constitutional rights, such as freedom of speech, were subject to the compelling-interest test. For example, a state could not pass a law stating that Native Americans are prohibited from using peyote, but it could accomplish the same result by prohibiting the use of peyote by everyone.

In the wake of Smith, many religious and civil liberties groups have worked to restore the Sherbert test — or compelling-interest test — through legislation. These efforts have been successful in some states. In other states, the courts have ruled that the compelling-interest test is applicable to religious claims by virtue of the state’s own constitution. In many states, however, the level of protection for free-exercise claims is uncertain.

Has the U.S. Supreme Court defined “religion?”

- The Supreme Court has never articulated a formal definition of religion.

- The Court has struggled to draw a line between religious beliefs and personal ethical and moral beliefs.

- While the Court has previously used Christian-centric standards to define “legitimate” religion, they have expanded their definition to include traditions that do not center around a higher power, such as secular humanism.

Although it has attempted to create standards to differentiate religious beliefs and actions from similar nonreligious beliefs, the Supreme Court has never articulated a formal definition for religion. Given the diversity of Americans’ religious experience since the Constitution was created, a single comprehensive definition has proved elusive.

In 1890, the Supreme Court in Davis v. Beason expressed religion in traditional Christian terms: “[T]he term ‘religion’ has reference to one’s views of his relations to his Creator, and to the obligations they impose of reverence for his being and character, and of obedience to his will.”

In the 1960s, the court expanded its view of religion. In its 1961 decision Torcaso v. Watkins, the court stated that the establishment clause prevents government from aiding “those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.” In a footnote, the court clarified that this principle extended to “religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God … Buddhism, Taoism, Ethical Culture, Secular Humanism and others.”

In its 1965 ruling United States v. Seeger, the court sought to resolve disagreement between federal circuit courts over interpretation of the Universal Military Training and Service Act of 1948. The case involved denial of conscientious objector status to individuals who based their objections to war on sources other than a supreme being, as specifically required by the statute. The Court interpreted the statute as questioning “[w]hether a given belief that is sincere and meaningful occupies a place in the life of its possessor parallel to that filled by the orthodox belief in God of one who clearly qualifies for the exemption. Where such beliefs have parallel positions in the lives of their respective holders we cannot say that one is ‘in relation to a Supreme Being’ and the other is not.”

Welsh v. United States represented another conscientious-objector case under the same statute. The court in this 1970 decision went one step further and essentially merged religion with deeply and sincerely held moral and ethical beliefs. The court suggested individuals could be denied exemption only if “those beliefs are not deeply held and those whose objection to war does not rest at all upon moral, ethical, or religious principle but instead rests solely upon consideration of policy, pragmatism, or expediency.”

Following the expansive view of religion expressed in Seeger and Welsh, the court in its 1972 ruling involving the Amish and compulsory school attendance suggested a shift back, to a more exclusive definition. The majority opinion in Wisconsin v. Yoder indicated that the free-exercise clause applied only to “a ‘religious’ belief or practice,” and “the very concept of ordered liberty precludes allowing every person to make his own standards on matters of conduct in which society as a whole has important interests.”

The court in its 1981 decision Thomas v. Review Board further expressed its reluctance to protect philosophical values. The Indiana Supreme Court had ruled that a decision by a Jehovah’s Witness to quit his job after he was transferred to a weapons-making facility was a “personal philosophical choice rather than a religious choice” and did not “rise to the level of a first amendment claim.” In overturning the Indiana decision, Chief Justice Warren Burger cautiously stated, “[o]nly beliefs rooted in religion are given special protection to the exercise of religion.” The court found the worker’s actions to be motivated by his religious beliefs.

Few have been satisfied by the court’s attempts to define religion. Many of the court’s definitions use the word “religion” to describe religion itself. In other cases, the court’s explanations seem to provide little useful guidance.

Prayer at Public School Events

Can a student pray at graduation exercises or at other school-sponsored events?

- In most cases, students may pray silently or aloud during a school-sponsored event as long as they are not causing a “significant disruption.”

- However, the First Amendment prohibits school-endorsed prayer, meaning public schools may not regularly and intentionally set time aside for prayer (such as an annual opening prayer at graduation) even if that prayer is student-led.

The free exercise clause of the First Amendment protects students’ rights to voluntarily pray at school-sponsored events, whether it is by themselves or in a group. That means if you, as a student, choose to say a prayer silently or aloud before, during or after the graduation ceremony, the Constitution protects your right to do so, if you are not causing a “significant disruption” to the ceremony.

The establishment clause, however, prohibits any form of school-endorsed prayer. This means an individual representing a public school — like a teacher, administrator or outside guest invited by the school — cannot lead prayer at graduation, even if student participation in the prayer is optional.

This precedent comes from Lee v. Weisman (1991), a case in which a Rhode Island family sued their public middle school for inviting clergy to lead prayer at graduation. The school defended the practice, arguing that neither participation in the prayer nor attendance at graduation itself were mandatory for students. But the Supreme Court disagreed, ruling that even though participation was technically optional the practice created “subtle and indirect coercion” to participate in government-led religious activity, thereby violating the establishment clause.

But what about student-led prayer? Can a school-designated student speaker lead a prayer while at the podium? Most likely, no.

In June 2000, the court ruled on Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, a case concerning student-led nonsectarian prayer conducted over the loudspeaker at a school-sponsored event. The court decided that even though it was a student leading the prayer, it still counted as government speech because it was a regularly held, school-endorsed practice occurring on government property. In other words, the Constitution prohibits public schools from regularly and intentionally setting time aside for prayer, even if that prayer is student-led and nonsectarian.

However, case law indicates student prayer can be permissible only in instances involving strictly student speech, and not when a student is conveying a message controlled or endorsed by the school. As the 11th Circuit case of Adler v. Duval County (2001) suggests, it would seem possible for a school to provide a forum for student speech within a graduation ceremony when prayer or religious speech might occur.

For example, a school might allow the valedictorian or class president an opportunity to speak during the ceremony. If such a student chose to express a religious viewpoint, it seems unlikely it would be found unconstitutional unless the school had suggested or otherwise encouraged the religious speech. (See Doe v. Madison School Dist., 9th Cir. 1998.) In effect, this means that in order to distance itself from the student’s remarks, the school must create a limited open forum for student speech in the graduation program.

If school officials feel a solemnizing event needs to occur at a graduation exercise, a neutral moment of silence might be the best option. This way, everyone could pray, meditate, or silently reflect on the previous year’s efforts in her own way.

Can a teacher pray at graduation exercises or at other school-sponsored events?

- The Constitution prohibits school-endorsed prayer. As representatives of the government, public school teachers and administrators’ ability to engage in prayer at school-sponsored events is limited to certain conditions.

- Teachers are permitted to conduct private, quiet prayers during school-sponsored events, even when in the presence of students, but they may not request or encourage students to partake in prayer.

- School officials must refrain from using their position in the public school to promote their outside religious activities.

Constitutional restrictions placed around teachers’ ability to freely exercise their religion in the classroom extend to any school sponsored events, including graduation ceremonies. As employees of the government, public school teachers and administrators are subject to the establishment clause and thus required to be neutral concerning religion while carrying out their duties. Of course, teachers and administrators — like students — bring their faith with them through the schoolhouse door each morning.

The First Amendment limits school staff’s ability to engage in prayer at graduation but does not fully prohibit it. According to Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, teachers are permitted to conduct private, quiet prayers during school sponsored events, even when in the presence of students. However, teachers may not request or encourage students to partake in prayer, or any other religious activity.

When not on duty and off school grounds, educators are free like all other citizens to practice their faith in full. But school officials must refrain from using their position in the public school to promote their outside religious activities.

Deeper Dive Into Prayer in Schools

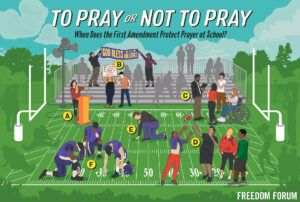

Infographic: To Pray or Not To Pray

Download a quick guide to common scenarios at school where prayer is protected expression – and where it is prohibited.

Read MoreKennedy v. Bremerton: A First Amendment Analysis

In its Kennedy v. Bremerton decision, the Supreme Court strengthened First Amendment protection for religious speech by government officials.

Read MoreFirst Amendment Facts: Graduation Ceremonies, Prayer and Religious Freedom

What students, parents and administrators should know about prayer in public schools.

Read MoreStudent Prayer in Schools

Is it legal for students to pray in public schools?

- Students are free to pray alone or in groups, if such prayers are not disruptive and do not infringe upon the rights of others.

- However, the right to engage in prayer does not include the right to have a captive audience or to compel others to join in prayer.

Yes. Contrary to popular myth, the Supreme Court has never outlawed “prayer in schools.” Students are free to pray alone or in groups, if such prayers are not disruptive and do not infringe upon the rights of others. But this right “to engage in voluntary prayer does not include the right to have a captive audience listen or to compel other students to participate.” (This is the language supported by a broad range of civil liberties and religious groups in a joint statement of current law.)

What the Supreme Court has repeatedly struck down are state-sponsored or state-organized prayers in public schools.

The Supreme Court has made clear that prayers organized or sponsored by a public school — even when delivered by a student — violate the First Amendment, whether in a classroom, over the public address system, at a graduation exercise, or even at a high school football game. (Engel v. Vitale, 1962; School Dist. of Abington Township v. Schempp, 1963; Lee v. Weisman, 1992; Santa Fe Independent School. Dist. v. Doe, 2000)

Can students express their beliefs about religion in classroom assignments or at school-sponsored events?

- Yes, students may express their beliefs about religion in classroom assignments—within certain limits.

- In most cases, if it is relevant to the subject under consideration, students should be allowed to express their religious or nonreligious views in the classroom.

Generally, if it is relevant to the subject under consideration and meets the requirements of the assignment, students should be allowed to express their religious or nonreligious views during a class discussion, as part of a written assignment, or as part of an art activity.

This does not mean, however, that students have the right to compel a captive audience to participate in prayer or listen to a proselytizing sermon. School officials should allow students to express their views about religion but should draw the line when students wish to invite others to participate in religious practices or want to give a speech that is primarily proselytizing. There is no bright legal line that can be drawn between permissible and impermissible student religious expression in a classroom assignment or at a school-sponsored event. In recent lower court decisions, judges have deferred to the judgment of educators to determine where to draw the line. (C.H. v. Olivia, 2nd Cir. 2000)

Is it constitutional for a public school to require a “moment of silence”?

- Yes, but only if the moment of silence is genuinely neutral. If a moment of silence is being used to promote prayer, it will be struck down by the courts.

Yes, if, and only if, the moment of silence is genuinely neutral. A neutral moment of silence that does not encourage prayer over any other quiet, contemplative activity will not be struck down, even though some students may choose to use the time for prayer. (See Bown v. Gwinnett County School Dist., 11th Cir. 1997)

If a moment of silence is used to promote prayer, it will be struck down by the courts. In Wallace v. Jaffree (1985) the Supreme Court struck down an Alabama “moment of silence” law because it was enacted for the express purpose of promoting prayer in public schools. At the same time, however, the Court indicated that a moment of silence would be constitutional if it is genuinely neutral. Many states and local school districts currently have moment-of-silence policies in place.

Teachers' Religious Liberty Rights

Can teachers and administrators pray or otherwise express their faith while at school?

- The Constitution prohibits school-endorsed religious activity. As representatives of the government, public school teachers and administrators’ ability to pray or express their faith at school is limited to certain conditions.

- Teachers are permitted to conduct private, quiet prayers during school, even in the presence of students, but they may not request or encourage students to partake in prayer.

- School officials must refrain from using their position in the public school to promote their outside religious activities.

As employees of the government, public school teachers and administrators are subject to the establishment clause and thus required to be neutral concerning religion while carrying out their duties. Of course, teachers and administrators — like students — bring their faith with them through the schoolhouse door each morning. According to Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), teachers are permitted to conduct private, quiet prayers even when in the presence of students. However, teachers may not request or encourage students to partake in group prayer, or any other religious activity.

If multiple teachers choose to meet for prayer or scriptural study in the faculty lounge during free time in the school day or before or after school, most legal experts see no constitutional reason why they should not be permitted to do so, if the activity does not interfere with their duties or the rights of other teachers.

When not on duty, of course, educators are free like all other citizens to practice their faith. But school officials must refrain from using their position in the public school to promote their outside religious activities.

The U.S. Department of Education put it this way in its 2003 guidelines on prayer in public schools:

“When acting in their official capacities as representatives of the state, teachers, school administrators, and other school employees are prohibited by the Establishment Clause from encouraging or discouraging prayer, and from actively participating in such activity with students. Teachers may, however, take part in religious activities where the overall context makes clear that they are not participating in their official capacities. Before school or during lunch, for example, teachers may meet with other teachers for prayer or Bible study to the same extent that they may engage in other conversation or nonreligious activities. Similarly, teachers may participate in their personal capacities in privately sponsored baccalaureate ceremonies.”

Can a teacher wear religious garb to school, provided the teacher does not proselytize to the students?

- While there is some flexibility on this issue, many courts allow schools to prohibit teachers’ religious garb in order to maintain religious neutrality.

Probably not. It is likely that many courts would allow a school to prohibit teachers’ religious garb in order to maintain religious neutrality. The courts may view such garb as creating a potential establishment-clause problem, particularly at the elementary school level.

Pennsylvania and Oregon have laws that prohibit teachers from wearing religious clothing to schools. Both laws have been upheld in court challenges brought under the First Amendment and Title VII, the major anti-discrimination employment law. The courts reasoned that the statutes furthered the states’ goal of ensuring neutrality with respect to religion in the schools.

In the Pennsylvania case, U.S. v. Board of Education, the 3rd Circuit rejected the Title VII religious-discrimination claim of a Muslim teacher who was prevented from wearing her religious clothing to school. The school acted pursuant to a state law, called the “Garb Statute,” which provided: “[N]o teacher in any public school shall wear in said school or while engaged in the performance of his duty as such teacher any dress, mark, emblem or insignia indicating the fact that such teacher is a member or adherent of any religious order, sect or denomination.”

The teacher and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission contended that the school should have allowed the teacher to wear her head scarf and long, loose dress as a “reasonable accommodation” of her religious faith. The appeals court disagreed, determining that “the preservation of religious neutrality is a compelling state interest.”

In its 1986 decision Cooper v. Eugene School District, the Oregon Supreme Court rejected the free-exercise challenge of a Sikh teacher suspended for wearing religious clothing — a white turban and white clothes — to her special education classes. The Oregon high court upheld the state law, which provided: “No teacher in any public school shall wear any religious dress while engaged in the performance of duties as a teacher.” The court wrote that “the aim of maintaining the religious neutrality of the public schools furthers a constitutional obligation beyond an ordinary policy preference of the legislature.”

The First Amendment Center’s A Teacher’s Guide to Religion in the Public Schools provides that “teachers are permitted to wear non-obtrusive jewelry, such as a cross or Star of David. But teachers should not wear clothing with a proselytizing message (e.g., a ‘Jesus Saves’ T-shirt).”

Can teachers wear religious jewelry in the classroom?

Most experts agree that teachers are permitted to wear unobtrusive jewelry, such as a cross or a Star of David. But they should not wear clothing with a proselytizing message (e.g., a “Jesus Saves” T-shirt).

How should teachers respond if students ask them about their religious beliefs?

- If asked about their religious beliefs, teachers may answer at most with a brief statement of personal belief but may not turn the question into an opportunity to proselytize for or against religion.

Some teachers prefer not to answer the question, believing that it is inappropriate for a teacher to inject personal beliefs into the classroom. Other teachers may choose to answer the question directly and succinctly in the interest of an open and honest classroom environment.

Before answering the question, however, teachers should consider the age of the students. Middle and high school students may be able to distinguish between a personal conviction and the official position of the school; very young children may not. In any case, the teacher may answer at most with a brief statement of personal belief — but may not turn the question into an opportunity to proselytize for or against religion. Teachers may neither reward nor punish students because they agree or disagree with the religious views of the teacher.

Can teachers or other school employees participate in student religious clubs?

- The Equal Access Act states that “employees or agents of the school or government are present at religious meetings only in a nonparticipatory capacity.”

For insurance purposes, or because of state law or local school policy, teachers or other school employees are commonly required to be present during student meetings. But if the student club is religious in nature, school employees may be present as monitors only. Such custodial supervision does not constitute sponsorship or endorsement of the group by the school.

Can a teacher refuse to teach certain materials in class if they feel the curriculum infringes on their personal religious beliefs?

- Generally, teachers must instruct their students in accordance with the established curriculum, regardless of their own personal religious beliefs.

Generally, teachers must instruct their students in accordance with the established curriculum. For example, the 9th Circuit ruled in 1994 against a high school biology teacher who had challenged his school district’s requirement that he teach evolution, as well as its order barring him from discussing his religious beliefs with students. In the words of the court, “[A] school district’s restriction on [a] teacher’s right of free speech in prohibiting [the] teacher from talking with students about religion during the school day, including times when he was not actually teaching class, [is] justified by the school district’s interest in avoiding [an] Establishment Clause violation.” (Peloza v. Capistrano Unified School Dist., 9th Cir. 1994)

Also, a state appeals court ruled again that a high school teacher did not have a First Amendment right to refuse to teach evolution in a high school biology class (LeVake v. Independent School Dist. No. 656, Minn. App. 2001). The teacher had argued that the school district had reassigned him to another school and another course because it wanted to silence his criticism of evolution as a viable scientific theory. The state appeals court rejected that argument, pointing out that the teacher could not override the established curriculum.

Other courts have similarly found that teachers do not have a First Amendment right to trump school district decisions regarding the curriculum (Clark v. Holmes, 7th Cir. 1972, Webster v. New Lenox School Dist. No. 122, 7th Cir. 1990, Boring v. Buncombe County Bd. of Education, 1998). One court wrote: “the First Amendment has never required school districts to abdicate control over public school curricula to the unfettered discretion of individual teachers.” (Kirkland v. Northside Independent School Dist., 5th Cir. 1989)

Religion in the Classroom

The First Amendment says that the government may not “establish” religion. What does that mean in a public school?

- The establishment clause requires public schools to be “neutral” toward religion.

- This means public schools may neither promote religious activity nor inhibit religious activity. They also may not favor one religion over the other, or religion over nonreligion.

In the past several decades, the Supreme Court has crafted several tests to determine when state action becomes “establishment” of religion. No one test is currently favored by a majority of the Court. Nevertheless, no matter what test is used, it is fair to say that the Court has been stricter about applying the establishment clause in public schools than in other government settings. For example, the Court has upheld legislative prayer (Marsh v. Chambers, 1983), but struck down teacher-led prayer in public schools (Engel v. Vitale, 1962). The Court applies the establishment clause more rigorously in public schools, mostly for two reasons: (1) students are impressionable young people, and (2) they are a “captive audience” required by the state to attend school.

When applying the establishment clause to public schools, the Court often emphasizes the importance of “neutrality” by school officials toward religion. This means that public schools may neither inculcate nor inhibit religion. They also may not prefer one religion over another — or religion over nonreligion.

If school officials are supposed to be ‘neutral’ toward religion under the establishment clause, does that mean they should keep religion out of public schools? No. By “neutrality” the Supreme Court does not mean hostility to religion. Nor does it mean ignoring religion. Neutrality means protecting the religious-liberty rights of all students while simultaneously rejecting school endorsement or promotion of religion.

In 1995, 24 major religious and educational organizations defined religious liberty in public schools this way: Public schools may not inculcate nor inhibit religion. They must be places where religion and religious conviction are treated with fairness and respect.

How should the Bible be included in the history curriculum?

- Learning about the history of the Bible, as well as the role of the Bible in history, are appropriate topics in a variety of courses in the social studies.

The study of history offers several opportunities to study about the Bible. When studying the origins of Judaism, for example, students may learn different theories of how the Bible came to be. In a study of the history of the ancient world, students may learn how the content of the Bible sheds light on the history and beliefs of Jews and Christians — adherents of the religions that affirm the Bible as scripture. A study of the Reformation might include a discussion of how Protestants and Catholics differ in their interpretation and use of the Bible.

In U.S. history, there are natural opportunities for students to learn about the role of religion and the Bible in American life and society. For example, many historical documents — including many presidential addresses and congressional debates — contain biblical references. Throughout American history, the Bible has been invoked on various sides of many public-policy debates and in conjunction with social movements such as abolition, temperance and the civil rights movement. A government or civics course may include some discussion of the biblical sources for parts of our legal system.

Learning about the history of the Bible, as well as the role of the Bible in history, are appropriate topics in a variety of courses in the social studies.

Can public schools offer a history course that focuses on the Bible?

- Yes, but the course must be designed using non-biblical sources from a variety of scholarly perspectives which engage in the complex debates about the historicity of the Bible.

- Teachers who teach a history course focused on the Bible need to be sensitive to the differences between conventional secular history and the varieties of sacred history.

- Unless schools are prepared to design a course that meets these requirements, they will face legal and educational challenges.

An elective history course that focuses on the Bible is a difficult undertaking for public schools because of the complex scholarly and religious debates about the historicity of the Bible. Such a course would need to include non-biblical sources from a variety of scholarly perspectives. Students would study archeological findings and other historical evidence in order to understand the history and cultures of the ancient world. Teachers who may be assigned to teach a history course focused on the Bible need a great deal of preparation and sophistication.

Unless schools are prepared to design a course that meets the above requirements, they will face legal and educational challenges. In view of these requirements, most public schools that have offered a Bible elective have found it safer and more age-appropriate to use the Bible literature approach.

Schools must keep in mind that the Bible is seen by millions of people as scripture. This means that the Bible may not be treated as a history textbook by public school teachers but must be studied by examining a variety of perspectives — religious and non-religious — on the meaning and significance of the biblical account.

As we have already noted, sorting out what is historical in the Bible is complicated and potentially controversial. Teachers who teach a history course focused on the Bible need to be sensitive to the differences between conventional secular history and the varieties of sacred history. Students must learn something about the contending ways of assessing the historicity of the Bible. They cannot be uncritically taught to accept the Bible as literally true, as history. Nor should they be uncritically taught to accept as historical only what secular historians find verifiable in the Bible.

Sometimes, in an attempt to make study about the Bible more “acceptable” in public schools, educators are willing to jettison accounts of miraculous events. But this too is problematic, for it radically distorts the meaning of the Bible. For those who accept the Bible as scripture, God is at work in history, and there is a religious meaning in the patterns of history. A Bible elective in a public school may examine all parts of the Bible, as long as the teacher understands how to teach about the religious content of the Bible from a variety of perspectives.

What about the study of other religious traditions?

- While the devotional study of religion is prohibited in public schools, the academic study of religious religion can and should be included in a public school education.

- Because religion plays a significant role in history and society, studying religion is essential to understanding both the nation and the world.

Given the importance and influence of religion, public schools should include study about religion in some depth on the secondary level. Public schools should also include study about other religious faiths in the core curriculum and offer electives in world religions. Because religion plays a significant role in history and society, study about religion is essential to understanding both the nation and the world. Moreover, knowledge of the roles of religion in the past and present promotes crosscultural understanding in our increasingly diverse society.

Some school districts require that high schools offering a Bible elective also offer an elective in world religions. There is considerable merit in this approach. This gives students an opportunity to learn about a variety of religions and conveys to students from faiths other than the biblical traditions that their religions are also worthy of study. It is important for public schools to convey the message that the curriculum is designed to offer a good education, and not to prefer any religious faith or group.

Can religious scriptures be used in a public school classroom?

- Religious scriptures can be used in the public school classroom to illuminate the influence of religion in society, but may not be used to promote devotional religious teaching.

- If using religious scripture in the classroom, selections should always be treated with respect and used only in the appropriate historical and cultural context.

- Teachers should alert students to the fact there are a variety of interpretations of scripture within each religious tradition.

Study of history or literature would be incomplete without exposure to the scriptures of the world’s major religious traditions. Some knowledge of biblical literature, for example, is necessary to comprehend much in the history, law, art and literature of Western civilization, just as exposure to the Quran is important for understanding Islamic civilization. In this sense, the classical religious texts are part of our study of history and culture.

At the same time, students need to recognize that, while scriptures tell us much about the history and cultures of humankind, they are considered sacred accounts by adherents to their respective traditions. Religious documents give students of history the opportunity to examine directly how religious traditions understand divine revelation and human values.

In a history class, selections from these accounts should always be treated with respect and used only in the appropriate historical and cultural context. Alert students to the fact that there are a variety of interpretations of scripture within each religious tradition.

Can teachers use role-playing or simulations to teach about religion?

- No, teachers should not use role-playing or simulations to teach about religion because, even if carefully planned, the lesson will likely be unconstitutional.

Recreating religious practices or ceremonies through role-playing activities should not take place in a public school classroom for three reasons:

- Such reenactments run the risk of blurring the distinction between teaching about religion (which is constitutional) and school-sponsored practice of religion (which is unconstitutional).

- Role-playing religious practices or rituals may violate the religious liberty, or freedom of conscience, of the students in the classroom. Even if the students are all volunteers, many parents don’t want their children participating in a religious activity of a faith not their own. The fact that the exercise is “acting” doesn’t prevent potential problems.

- Simulations or role-playing, no matter how carefully planned or well-intentioned, risk trivializing, caricaturing or oversimplifying the religious tradition that is being studied. Teachers should use audiovisual resources and primary sources to introduce students to the ceremonies and rituals of the world’s religions.

Is it legal to invite guest speakers to help teach about religion?

- Yes, it is legal to invite guest speakers to help teach about religion if the school district policy allows guest speakers in the classroom.

- Care should be taken to find someone with the academic background necessary for an objective and scholarly discussion of the historical period and the religion under consideration.

If a guest speaker is invited, care should be taken to find someone with the academic background necessary for an objective and scholarly discussion of the historical period and the religion under consideration. Faculty from local colleges and universities often make excellent guest speakers, or they can recommend others who might be appropriate for working with students in a public school setting. Religious leaders in the community may also be a resource. Remember, however, that they have commitments to their own faith. Above all else, be certain that any guest speaker understands the First Amendment guidelines for teaching about religion in public education and is clear about the academic nature of the assignment.

What are the academic aims of a literature elective in the Bible?

- The primary aim of a literature elective in the Bible would be basic biblical literacy — a grasp of the language, major narratives, symbols and characters of the Bible.

A literature elective in the Bible would focus on the Bible as a literary text. This might include the Bible as literature and the Bible in literature. A primary goal of the course would be basic biblical literacy — a grasp of the language, major narratives, symbols and characters of the Bible. The course might also explore the influence of the Bible in classic and contemporary poems, plays and novels.

Of course, the Bible is not simply literature — for a number of religious traditions it is scripture. A “Bible Literature” course, therefore, could also include some discussion of how various religious traditions understand the text. This would require that literature teachers be adequately prepared to address in an academic and objective manner the relevant, major religious readings of the text.

How should the Bible be included in the literature curriculum?

Academic study of the Bible in a public secondary school may appropriately take place in literature courses. Students might study the Bible as literature. They would examine the Bible as they would other literature in terms of aesthetic categories, as an anthology of narratives and poetry, exploring its language, symbolism and motifs. Students might also study the Bible in literature, the ways in which later writers have used Bible literature, language and symbols. Much drama, poetry and fiction contains material from the Bible.

How should teachers of a Bible elective be selected and what preparation will they require?

- School districts and universities should offer in-service workshops and summer institutes for teachers who are teaching about the Bible in literature and history courses.

- When selecting teachers to teach Bible electives, school districts should look for teachers who have some background in the academic study of religion.

Teaching about the Bible, either in literature and history courses or in Bible electives, requires considerable preparation. School districts and universities should offer in-service workshops and summer institutes for teachers who are teaching about the Bible in literature and history courses.

When selecting teachers to teach Bible electives, school districts should look for teachers who have some background in the academic study of religion. Unless they have already received academic preparation, teachers selected to teach a course about the Bible should receive substantive in-service training from qualified scholars before being permitted to teach such courses. Electives in biblical studies should only be offered if there are teachers academically competent to teach them.

For the future, we recommend changes in teacher education to help ensure that study about religion, including the Bible, is done well in public schools. Literature and history teachers should be encouraged, as part of their certification, to take at least one course in religious studies that prepares them to teach about religions in their subject. Teachers who wish to teach a Bible elective should have taken college-level courses in biblical studies. Eventually, religious studies should become a certifiable field, requiring at least an undergraduate minor. State departments of education will need to set certification requirements, review curricula, and adopt appropriate academic standards for electives in religious studies.

Which version of the Bible should be used?

- There is no single, definitive Bible and to adopt any particular Bible or translation is likely to suggest to students that it is normative, the best Bible.

- One solution is to use a biblical sourcebook that includes the key texts of each of the major Bibles or an anthology of various translations.

Selecting a Bible for use in literature, history or elective Bible courses is important, since there is no single Bible. There is a Jewish Bible (the Hebrew Scriptures, or Tanakh), and there are various Christian Bibles — such as Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox — some with additional books, arranged in a different order. These differences are significant. For example, Judaism does not include the Christian New Testament in its Bible, and the Catholic Old Testament has 46 books, while the Protestant has 39. There are also various English translations within each of these traditions.

To adopt any particular Bible — or translation — is likely to suggest to students that it is normative, the best Bible. One solution is to use a biblical sourcebook that includes the key texts of each of the major Bibles or an anthology of various translations. At the outset and at crucial points in the course, teachers should remind students about the differences between the various Bibles and discuss some of the major views concerning authorship and compilation of the books of the Bible. Students should also understand the differences in translations, read from several translations, and reflect on the significance of these differences for the various traditions.

Dive Deeper Into Religion and the Curriculum:

Perspective: Public Schools Need Constitutional and Religious Literacy

Public schools are bound by the First Amendment to protect these rights.

Read MoreA First Amendment Framework for Effective Dialog in the Classroom

A constitutional framework teaches students effective dialog and understanding across differences.

Read MoreA National Summit on Religion and Education

Experts explored how to improve religious studies education in the United States.

Read MoreFunding for Religious Schools

Can my state pass a voucher program in which some vouchers are used at religious schools?

- Yes, a state is allowed to pass a voucher program in which some vouchers are used at religious schools.

- Voucher programs must be neutral to religion, meaning the state cannot prohibit citizens from using vouchers at certain private schools simply because the school is religious.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Zelman v. Simmons-Harris that, under certain conditions, communities may create a voucher program for use at a variety of schools without violating the U.S. Constitution, even if some of the vouchers are redeemed at religious schools.

Citing precedent, Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s plurality opinion looked first at the purpose of a voucher program: It must exist for a valid secular purpose and not to promote any particular religion. The court’s analysis then focused on whether a voucher program advances religion. The justices agreed that a neutral benefit program could be constitutional, even if religious institutions received some of the funds.

The court indicated that communities must consider several factors when creating a voucher program:

- Is the proposed voucher program neutral with respect to religion? If the plan favors one religion over another, or nonreligion over religion, then it will violate the establishment clause.

- Will the vouchers be made available to students based on religiously neutral criteria? That would mean deciding who gets a voucher must be based on such nonreligious bases as financial need or attendance at poorly performing school, etc. Also, the schools that are allowed or not allowed to receive vouchers must similarly be appraised based on secular criteria, such as academic performance and ability to adhere to safety codes.

- The voucher must be awarded to an individual, not the religious institution, and the individual must, through private choice, make the decision as to where the voucher is to go. The government cannot influence this decision. This is necessary to demonstrate the government voucher is going to benefit the individual — as opposed to benefiting religion. This last element was by far the most contentious issue for the justices in the Zelman decision.

The ability of religious schools to receive voucher funding was further strengthened in Carson v. Makin (2022), in which the court struck down Maine’s policy of prohibiting sectarian schools from receiving voucher funds as religious discrimination. The court decided that while Maine did not have to offer tuition assistance to the public, once they did, they could not disqualify certain schools simply because they are religious.

While all the above material focuses on whether a voucher program is legal under the federal establishment clause, states must also look at their state constitutions. Most states have their own constitutional prohibitions against providing public funds to religious entities. These restrictions are often more restrictive than the U.S. Constitution.

Religious Symbols in Public Space

Are religious displays on public property — such as Ten Commandments in historical-documents exhibits — legal?

- The constitutionality of religious displays on government property is a very complicated legal issue, and there are many seemingly conflicting rulings.

- There is no single test to determine the constitutionality of religious displays on public property, although both the Lemon test and the endorsement test have been used in the past.

- In order to determine the legality of a religious display, the courts commonly consider factors such as funding sources, perceptions of “secularity,” and historical context of the display.

The question of whether a religious display on government property is constitutional requires a multi-step analysis. First, one should ask, who is funding and erecting the display? If a private group wants to place a religious monument on public property, then a free-expression analysis should be conducted, looking into such things as the type of forum in question. If a government entity is attempting to post a religious document, then a separate line of questions must be raised.

Religious displays on public property can be legal, but they must pass constitutional muster by not violating the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which requires government “neutrality” towards religion. In deciding whether religious displays violate the establishment clause, courts generally look to the Lemon test and the endorsement test.

The Lemon test poses three questions:

- Did the state actor have a secular purpose in posting the documents?

- Was the primary effect of the action to advance or promote religion?

- Was there excessive entanglement between government and religion in the given activity?

The government conduct must survive all three of these prongs if the action is to survive constitutional muster.

It is important to note the Lemon test is no longer used by the Supreme Court, but it is still in use in lower courts to determine establishment violations.

A more recent test that has gained popularity in the courts is the endorsement test. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor first outlined this test in her concurring opinion in the 1983 decision Lynch v. Donnelly, which involved a city-owned holiday display containing religious elements in a Pawtucket, R.I., park. This approach examines the following questions: Did the state actor subjectively intend to promote religion through its actions, and would the reasonable observer interpret the actions of the state as an endorsement of religion?

The elements of both tests should be examined before a government representative posts any religious documents or engages in other forms of religious expression.

Two cases decided in June 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court illustrate how even the high court can reach very different conclusions in ruling on seemingly similar religious-display cases. Both McCreary County v. ACLU and Van Orden v. Perry involved displays of the Ten Commandments on public property. In writing for the 5-4 majority in McCreary, Justice David Souter used the Lemon test and determined that the Ten Commandments displays in the two Kentucky courthouses conveyed a religious message to the public, failing to satisfy the first prong of the Lemon test that the display must have a secular purpose. Therefore, the Court majority found the displays in McCreary were unconstitutional.

In Van Orden, which was decided on the same day as McCreary, the high court ruled that a Ten Commandments monument on the Texas State Capitol grounds was constitutional. Chief Justice William Rehnquist, in writing the plurality opinion for the Court, quickly dismissed the Lemon Test, instead focusing on the nature and setting of the monument. The monument was part of a larger display containing 17 monuments and 21 historical markers celebrating the “people, ideals, and events that compose Texan identity.” In determining that the monument was of a secular purpose, and therefore constitutional, Justice Stephen Breyer in his concurring opinion noted that because the monument had been on display for 40 years before being challenged, it “suggests more strongly than can any set of formulaic tests that few individuals, whatever their system of beliefs, are likely to have understood the monument amounting, in any significantly detrimental way, to a government effort to favor a particular religious sect.”

Later that same year, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held in ACLU v. Mercer County that another Kentucky County courthouse Ten Commandments display was constitutional. In this case, a Mercer County resident had requested permission to hang a display titled “Foundations of American Law and Government” in the courthouse. The display included the Ten Commandments, Mayflower Compact, Declaration of Independence, Magna Carta, Star-Spangled Banner, Bill of Rights and other historical documents. The 6th Circuit affirmed the lower court’s ruling that because the Ten Commandments was part of an exhibit and was not, in any way, more prominently displayed than any of the other documents, the display had a secular purpose in educating the public rather than endorsing religion.

In Shurtleff v. City of Boston (2022), the court upheld the right for a private organization to fly a flag with Christian symbols outside of a government building as part of a citywide flag raising program. The program permitted hundreds of private groups in the state of Massachusetts to request their flag be raised outside of City Hall for a limited period. In a 9-0 decision, the court argued a reasonable observer would not view these flags as government speech, therefore, to prohibit a flag simply on the grounds it featured religious symbols would constitute viewpoint discrimination.

Are religious holiday displays on public property constitutional?

- It depends. The constitutionality of religious holiday displays on public property is measured on a case-by-case basis, often determined by the slightest change in facts.

- A religious holiday display on public property is less likely to violate the establishment clause if it is accompanied by other secular symbols.

- Two major cases concerning this issue (Lynch v. Donnelly and Allegheny v. ACLU) feature similar facts but were decided differently, resulting in somewhat inconsistent rulings in the lower courts.

It depends. Determining the constitutionality of religious holiday displays requires an analysis that is heavily “fact-driven,” meaning the slightest change in facts could completely change whether a holiday display is constitutional.

Three U.S. Supreme Court cases deal specifically with this question. In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the court held that a city-sponsored crèche in a public park did not violate the establishment clause because the display included other “secular” symbols, such as a teddy bear, dancing elephant, Christmas tree, and Santa Claus house. In Allegheny v. ACLU (1989), the court found that a Nativity scene in a county courthouse accompanied by a banner that read “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” (“Glory to God in the Highest”), was unconstitutional because it was “indisputably religious,” rather than secular, in nature. In 1995 in Capitol Square Review & Advisory Board v. Pinette, the court held that a private group of individuals (in this case the Ku Klux Klan) could erect a cross in the Ohio statehouse plaza during the holiday season. In reaching its decision, the court heavily relied on the fact that the KKK had requested permission to display the cross in the same manner as any other private group was required to do, that the public park had often been open to the public for various religious activities, and that the KKK expressly disclaimed any government endorsement of the cross with written language on the cross.

Despite the Supreme Court’s providing these baseline principles in religious holiday display cases, courts around the country have a difficult time in their application. For example, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held that a holiday display in a government building violated the establishment clause because the display lacked sufficient secular content. Included in the display was a Nativity scene, Christmas tree and Santa Claus. (Amancio v. Town of Somerset, 28 F. Supp. 2d 677 (D. Mass. 1998).) Contrast that decision with a ruling out of the 8th Circuit in which it was held that a holiday display that contained candy canes, a Christmas tree, snowman, wrapped gifts and a crèche was constitutional. (ACLU v. City of Florissant, 186 F.3d 1095 (8th Cir. 1999).) The 1st Circuit and 8th Circuit clearly are split, illustrated by these two decisions, in how to interpret Lynch and Allegheny.

Some circuits, however, have applied the trio of cases with great consistency. For example, the 3rd Circuit has held that a display depicting a Hanukkah menorah, Christmas trees, Kwanzaa candles, a sled and Frosty the Snowman, among other things, was constitutional. (ACLU v. Schundler, 168 F.3d 92 (1999).) This court adhered strictly to the decisions in Lynch and Donnelly in reaching its decision. The 2nd Circuit also reached a similar decision in a holiday display case that included a crèche, Christmas tree, Hanukkah menorah and a posted sign that stated that the display was privately sponsored. (Elewski v. City of Syracuse, 123 F. 3d 51 (2nd Cir. 1997).)

How can an individual ensure that a religious holiday display that she erects is constitutional?

First of all, any holiday display erected on private property is immune from any constitutional challenges. Secondly, if an individual or group of individuals decide to set up a holiday display on public property (i.e. parks, courthouses, town halls, etc) he should petition the appropriate authorities for authorization to erect such a display. If the site has been home to a variety of religious displays in the past, it is likely permission will be granted.

Dive Deeper into Religious Symbols

Vaccines

Which states require immunizations for public schoolchildren, and which offer religious exemptions?

All states currently require children to follow at least some form of standardized immunization schedule in order to be enrolled in public school. Vaccinations often required by this schedule include those against diphtheria, whooping cough, and the measles. Of the 50 states, all offer some exemptions for religious opposition to vaccination except Mississippi and West Virginia.

Has the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of religious exemptions to state-compelled vaccination?

No Supreme Court ruling explicitly establishes a position on religious exemptions to state-compelled vaccination. However, it is clear from the court’s establishment-clause rulings that it is unlikely for all such exemptions to be found in violation of the First Amendment. What is less clear is whether or not the court would find the free-exercise clause to mandate the inclusion of religious exemptions. For this reason, the status of religious exemptions to state-compelled vaccinations is still very much unclear. What the court has found, however, is that a state has the authority to require its citizens to receive certain inoculations. This authority was established in 1905 in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, where the court ruled that Massachusetts had the authority to require its citizens to be inoculated against smallpox.

How are exemption requests evaluated?

States generally apply one of three standards for evaluating religious-exemption requests.

- Parents requesting the exemption must be a member of a recognized religious organization that is opposed to vaccination.

- Parents must demonstrate a sincere and genuinely held religious belief that opposes one or all vaccinations.

- Parents must simply sign a statement confirming that they are religiously opposed to vaccination and would like an exemption.

Are religious exemptions the only way to opt out of mandatory vaccination?

No, all states include a medical exemption in their vaccination policy, and almost half of the states offer philosophical exemptions in addition to their medical and religious accommodations.

Dive Deeper in Religion and Vaccines:

Perspective: Divided Court Considers Religious Exemptions to Vaccine Mandates

There are no easy answers in weighing how best to balance public health and religious freedom concerns.

Read MorePerspective: Tide May be Turning Toward Religious Exemptions From Vaccine Mandates

Courts seem increasingly reluctant to enforce government mandates when faced with religious objections.

Read MoreReligious Protections in the Midst of a Pandemic: Two Key Arguments

What courts consider in weighing religious rights and public health restrictions.

Read MoreThe Two Big G’s – God and Government

In troubled times many religious communities find themselves reaching out to both God and government.

Read More