Is Hate Speech Illegal?

Freedom of speech is the best-known First Amendment freedom. But free speech faces important and often controversial questions, especially around hostile or hateful expression — commonly referred to as hate speech. But what exactly is hate speech? Is hate speech illegal? Is it protected by the First Amendment? Are there any exceptions? What about cross burning, antisemitism, and hate speech on college campuses and online?

We answer those questions, and much more, in this guide.

Is hate speech illegal in the United States?

In the United States, hate speech is not illegal — though sometimes hateful speech may lose First Amendment free speech protection for other reasons. To understand the difference, let’s define hate speech.

The United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.”

So, is hate speech any idea or view that is not mainstream? Is it speech that offends or insults a particular person or group? Or must it go further and cause harm to the target? Free speech experts have a variety of views. But U.S. law does not define or limit hate speech.

Is hate speech illegal? How does it apply to the First Amendment? Are there any exceptions?

— Freedom Forum (@1stForAll) August 29, 2023

➡️ https://t.co/jkbE77xLaR pic.twitter.com/oRBD5lgZCg

When can hateful speech or conduct be illegal?

In the U.S., hate speech is not categorically illegal. But while the First Amendment protects even inflammatory or derogatory speech, some types of such speech and some discriminatory, abusive or violent behavior can be illegal.

Hateful speech can sometimes also be an unprotected type of speech

Some categories of speech are not protected by the First Amendment, and these kinds of speech may overlap with speech considered to be hateful. A few of these are:

- Defamation: knowingly false statements that harm someone’s reputation.

- Inciting imminent lawless action: telling people to immediately commit a crime.

- True threats: knowingly causing someone to fear for their safety.

- Fighting words: words intended to provoke a violent reaction.

Importantly, speech that is not protected by the First Amendment is not judged on the viewpoint expressed but rather based on specific, narrow definitions and the direct harm the speech inflicts.

Hateful conduct can sometimes be criminal

Conduct that goes beyond words can be punished. Again, this is because some other law has been violated, not simply because of the message being conveyed. For example, vandalism and graffiti are punished not because of any message or viewpoint expressed, but rather because they damage people’s property, whether it’s a spray-painted happy face or a hateful slur.

Discrimination vs. hate speech

Many federal and state laws prevent discrimination in workplaces and businesses. The United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission explains that Title VII of the federal civil rights act says:

Applicants, employees and former employees are protected from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, or gender identity), national origin, age (40 or older), disability and genetic information (including family medical history).

Title II of that law says that businesses are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin. Each of the fifty states and the District of Columbia has a similar law, though they vary in terms of which characteristics are protected and in what situations.

Finding a balance between these laws and the First Amendment is often difficult. Antidiscrimination laws protect against acts of discrimination — an employer cannot refuse to hire a woman, a business owner cannot refuse service to a minority customer — but do not allow for punishment where those same employers or business owners simply express their views, even if that speech may be offensive or hateful. While the U.S. Supreme Court has held that business owners are not required to express messages that run contrary to their beliefs, they are not allowed to simply turn away customers based on those protected characteristics.

Hate crimes vs. hate speech

The federal government and most states have laws criminalizing “hate crimes.” The Department of Justice explains agency’s power to enforce “federal hate crimes laws that cover certain crimes committed on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability,” and also provides an overview of the state laws. Such laws have also been upheld against First Amendment challenges because they punish the criminal act that has occurred, not the criminal’s beliefs, words or other manner of expression.

Why is hate speech legal?

The First Amendment is designed to protect the most speech possible from government interference. Political speech is particularly protected from government regulation so that people are as free as possible to participate in public conversations about how we wish to be governed.

Freedom of speech is also designed to protect speech of all viewpoints. Laws that punish one point of view but don’t punish other viewpoints — referred to as viewpoint discrimination — are among the clearest violations of the First Amendment.

Laws prohibiting hate speech are almost always considered viewpoint discrimination because they only punish speech that is directed against a certain group. So political speech and speech from viewpoints that might be considered hateful cannot be made illegal.

Government bodies sometimes try to make hate speech illegal because officials or legislators disagree with the hateful speech they want to ban, but such laws must meet high First Amendment standards and often fail to prove in court that they are consistent with free speech.

Is cross burning illegal?

One example is laws prohibiting cross burning. The Supreme Court struck down a St. Paul, Minn., ordinance that criminalized cross burning intended to “arouse anger or alarm on the basis of race, color, creed or religion” in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul in 1992 because that law singled out people with particular viewpoints for punishment but didn’t punish people who might burn crosses for a different reason — or no reason at all. It wasn’t the act of burning the cross that was punished but the viewpoint the cross burning expressed. By comparison, a Virginia law prohibiting cross burning with an intent to intimidate others was upheld in Virginia v. Black in 2003 because it could be applied to anyone, regardless of viewpoint, who burned the cross to send a threatening message.

Is hate speech allowed on college campuses?

Hate speech on college campuses has also proven tricky. Many colleges and universities have codes of conduct designed to limit harassment and make their campuses more welcoming learning environments free from disruption. These codes of conduct — sometimes even overtly referred to as “speech codes” — often draw from the 1942 Supreme Court case Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, which created the “fighting words” exception to the First Amendment for face-to-face speech intended to provoke a violent response. In reality, these codes often go much further in practice, calling their constitutionality into question.

Is antisemitism illegal?

Like other forms of hate speech, antisemitism — prejudice or hatred against those of Jewish faith — is generally protected under the First Amendment. But antisemitism loses free speech protections for the same reasons as other hate speech: when it incites violence or represents a true threat, for example.

It also depends on where this speech occurs. Colleges and universities that receive federal funding often have codes of conduct designed to meet the schools’ obligations under federal civil rights law. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act prohibits any institution that receives federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race, color and national origin, which has been interpreted to include shared Jewish ancestry. Universities may seek to discipline students for antisemitic speech, sometimes under pressure from the federal government in cases where the school receives federal funding. But for public universities, these codes of conduct, as well as any other attempts to enforce violations of Title VI, must comply with the First Amendment. This means that antisemitic statements are protected unless they rise to the level of harassment or discrimination, often because they interrupt another student’s educational process.

Is hate speech allowed online?

In recent years, hate speech has proliferated online with social media platforms in particular struggling to balance a commitment to free speech with a desire to maintain decorum. Because the First Amendment does not apply to private businesses, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and others can remove users based on the content — hateful or otherwise — of their posts as long as they comply with their own terms of use. Further, they cannot be sued if they decide to let that same content — hateful or otherwise — remain on the platform because Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act immunizes them from liability based on their users’ posts.

RELATED: Free speech on social media: The complete guide

Would making hate speech illegal protect or damage freedom of speech?

One argument for reconsidering whether hate speech should be legal is that laws to curb hate speech would enable people to feel freer to participate in public conversations without the potential for hateful backlash, thereby actually protecting free speech. Such laws could limit the ways hateful speakers shut down or scare others so that they are too afraid to speak.

To Thane Rosenbaum, distinguished university professor at Touro University, hate speech can be objectively identified: It’s when speech or expression is no longer trying to convey an idea or message, but aimed only at shutting others down. For Rosenbaum, hate speech is an act of violence to intimidate, scare and ensure others are too afraid to participate in conversation. According to Rosenbaum, though hate speech is not illegal in the United States, it would protect vulnerable and marginalized communities better to limit hateful speech and protests in the United States.

Many countries around the world share this view and have laws making hate speech illegal, unlike the United States. Hate speech is restricted in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and Germany, among others. Laws making hate speech illegal around the world often criminalize hate-motivated speech that incites violence or that harms people’s dignity.

In a 9-1 ruling, Brazil's Supreme Court has ruled that homophobic hate speech is now punishable by prison.

— Pop Crave (@PopCrave) August 24, 2023

The ruling puts homophobic hate speech at the same legal level as racist hate speech, which was already punishable by prison in the country. pic.twitter.com/fXUR48BZcb

Rosenbaum says, “The enemy of free speech is no longer the government. It’s the people.”

However, Nadine Strossen, former president of the American Civil Liberties Union and New York Law School’s John Marshall Harlan II professor of law, emerita, says because hate is an emotion, hate speech is subjective. What one person might consider loving words, someone from a different background with different beliefs could see as hate. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to regulate. But Strossen says that laws should only limit behaviors, not beliefs, which requires protecting even abhorrent speech.

Strossen and others argue hate speech laws are “very blunt tools.” Even if well-intentioned, where they have been tried in practice, they tend to be used to limit the rights of the very people they’re designed to protect — like those who disagree with government. And they don’t successfully limit hateful ideologies.

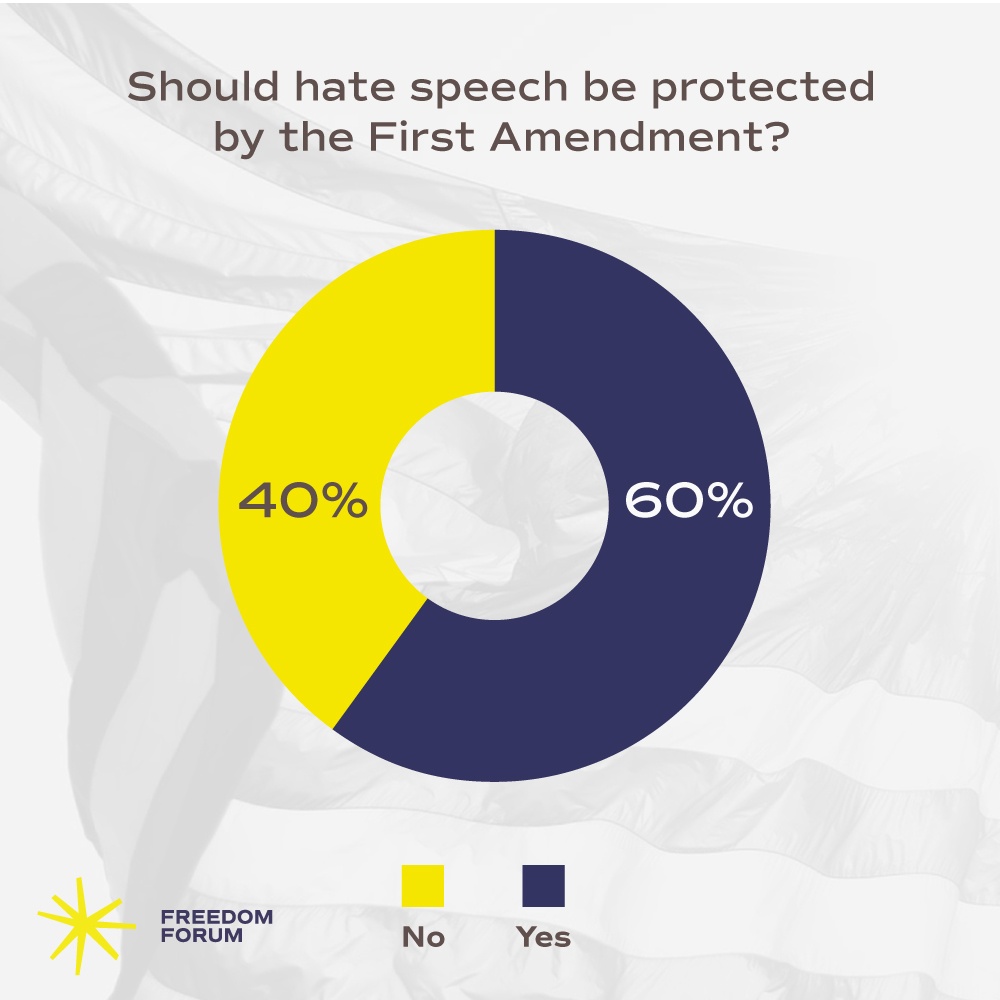

What do Americans think about whether hate speech should be legal?

According to Freedom Forum surveys, about 6 in 10 Americans know that hate speech is legal under the First Amendment.

However, about 4 in 10 survey respondents say that preventing hate speech is more important than protecting free speech. About the same number say that hate speech should be illegal. Women, people of color and younger people were more likely than older white men to favor limits on offensive or hateful speech.

Of survey respondents who would ban hate speech, just over half say that hate speech should be illegal because it can expose targeted groups to discrimination, abuse or violence. Others who argue for hate speech to be illegal say such speech denies tolerance, inclusion and diversity and fosters exclusion.

Among those who would ban hate speech, most say determinations about what constitutes hate speech should be made at the national level. Five in 10 say the Supreme Court should have the final say about when hate speech is illegal. A small percentage would favor state-level decisions or local control.

Our Where America Stands survey shows that 60% of Americans believe hate speech should remain protected by the First Amendment.

Six in 10 Americans say hate speech should remain protected by the First Amendment. Of those, about half say hate speech is a matter of interpretation, so regulation would lead to selective enforcement by whoever happens currently to be in power. Others say the best response to objectionable speech is more speech or that hate speech standards could change over time.

What’s the bottom line about the First Amendment and whether hate speech is illegal?

So, is hate speech illegal? In short, no. The First Amendment protects hate speech from government interference.

But if hateful speech happens to fit into an unprotected category of speech, it may be punishable by law. Private people and organizations, such as social media companies, can also make their own decisions about what speech to allow in their spaces. And people can respond to hate speech by speaking out against it and supporting the people it targets.

This article was updated April 15, 2025. It may be updated with future developments.

Kevin Goldberg, First Amendment specialist for the Freedom Forum, contributed to this article. He can be reached at kgoldberg@freedomforum.org.

Son of Sam Laws: Do Criminals Have a Right to Profit From Their Crimes?

What Is Separation of Church and State?

Related Content