Perspective: Post-Roe Predictions for Religious Freedom

Abortion is an issue at the center of America’s raging culture wars, and with the leak of Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion curtailing abortion rights, the stakes just got even higher. There are explosive possibilities not just for abortion rights but also the First Amendment right to religious liberty, which in recent years has been tightly bound up with abortion politics.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case at the center of the leaked opinion, involves a Mississippi law that bans abortion with nearly no exception after the 15th week of pregnancy.

The timeline is significantly different from that set by previous cases.

Abortion law under Roe

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the Supreme Court held that the right to privacy included the right to abortion and permitted varying levels of regulation depending on the pregnancy trimester:

- During the first trimester (up to 12 weeks), governments could not ban abortion at all.

- During the second trimester (13 to 26 weeks), reasonable health regulations were permissible.

- During the final trimester (after 26 weeks), governments could ban abortion entirely with narrow exceptions for the health or life of the mother.

Court modifies Roe standard in Casey

The court struck down that trimester framework two decades later in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), even as it reaffirmed Roe’s holding that abortion rights were inherent to the right to privacy. In place of the trimester framework, in Casey, the court held that a fetal viability standard worked better and set the cutoff at around 24 weeks. Casey said that state laws that ban abortion prior to fetal viability create an undue burden on the woman seeking an abortion and are unconstitutional.

Where abortion law could go now

Dobbs calls Roe and Casey into question. The issue in the case is whether all prohibitions on pre-viability abortions are unconstitutional. During oral arguments, the attorney for Mississippi said Casey’s viability standard is “not the world the Constitution promises.” Justice Alito’s leaked opinion gets at it even more directly: “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision.”

What’s next for religious liberty?

So, where (and whether) the Constitution draws the line is the core issue in the case. But so much more is at stake, including for constitutional rights such as the right to religious liberty.

As one of the 140 amicus briefs filed in Dobbs argues, the Roe/Casey framework is singularly responsible for inflaming religious liberty conflicts. Religious freedom protective statutes like the Religious Freedom Restoration Act once enjoyed broad, bipartisan support. Today that coalition is deeply fractured in large part because of abortion politics, which tends to be closely tied with other areas of reproductive autonomy, such as contraceptive use.

The brief — filed by the prominent religious liberty advocacy firm, Becket Law — points to the national fury over cases like Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, which involved a religion-based challenge to the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that employers pay for their employees’ access to the morning- and week-after contraceptive pills. Religious challengers contended the drugs are abortion-causing. Similarly, Becket points out that pharmacists who object on religious grounds to dispensing these contraceptives have faced hostile lawmakers “acting at the behest of abortion advocates.” In Washington, for example, pharmacists were required to dispense the pills even as the state permitted a host of other exceptions.

Today, this hostility makes it nearly impossible to build religious freedom coalitions across political lines. And the conditions won’t improve, the brief argues, unless the Roe/Casey framework is replaced with a political solution. When legislators are given the opportunity, they tend to craft compromise solutions that balance the diverse interests at stake. As evidence, Becket points to the pre-Roe status quo and the experiences of European countries that have significantly lower levels of social strife because they permit careful legislative compromises that account for religious interests.

Others say the court striking down Roe threatens to create more social strife. They argue that America’s diverse faith communities hold sharply divergent perspectives on abortion. Striking down Roe prioritizes some Christians’ religious beliefs while violating the rights of those religious believers — such as Jews and Muslims — whose religions permit abortion at later stages of pregnancy or more highly prioritize the mother’s well-being. As one advocate explained, “[T]here is a long tradition in this country of faith-based activists, health care providers, and others advocating for the full range of reproductive health care … The right doesn’t get to own religion, and it certainly shouldn’t when it comes to the law.”

One solution to this last concern is to grant dissenting believers an exemption from laws banning abortion. But the political landscape suggests that is unlikely. Religious objectors to contraception have faced difficulty in obtaining exceptions to requirements to provide it. Meanwhile, in the view that abortion constitutes murder, there are no religious exceptions.

So, one side thinks striking down Roe/Casey is the solution to our First Amendment religious liberty battles, and the other side thinks it’s the beginning of much greater strife. Which side is right will be apparent soon enough; the court’s final opinion is expected this summer.

Asma T. Uddin is senior fellow for religious liberty at the Freedom Forum.

Watch: First Five Now: The Supreme Court and Religious Freedom

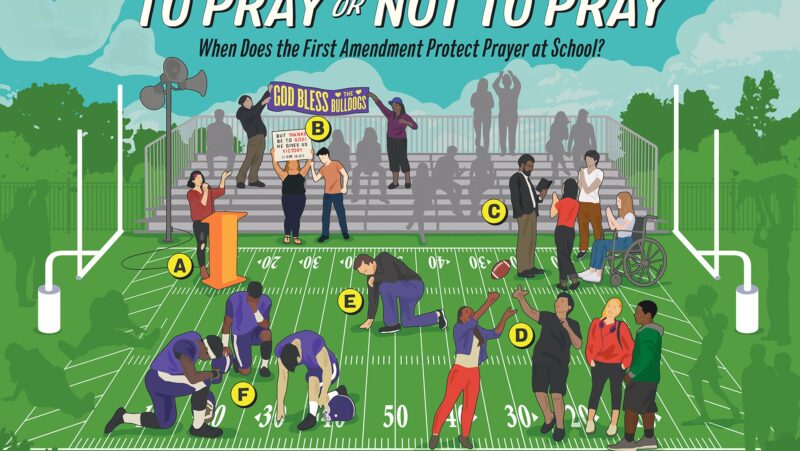

Infographic: To Pray or Not To Pray

Related Content