Recording in Public: Is It Illegal to Record Without Permission?

Is recording in public protected by the First Amendment? Can you make a video or audio recording anytime and anywhere you want of someone or something that you can see?

Well, in theory: Yes, you can.

But the reality is that the specifics of recording in public – and what you can do with a recording – can get complicated, very quickly.

The general rule of thumb is that your ability to record in any situation is dependent on the subject's "reasonable expectation of privacy." That expectation might change depending on where, who and why you are recording.

Where is recording in public permitted or limited?

Recording something in plain view, in a public space like a street or public park, is generally allowed. But all public spaces are not created equal – and some may not be "public" after all.

Recording in public buildings

Courts have approved limits or even bans on recordings in certain government buildings and spaces if these rules are for security purposes or to maintain order in hallways or during meetings.

Recording in publicly accessible but privately owned spaces

Courts also have set out a mix of rules and exceptions that apply to recording in spaces that are publicly accessible but are privately owned, such as shopping malls. Start with the idea that such private spaces have a right to set their own policies.

Note for commercial filmmaking in parks: Commercial filmmakers are required to get a permit to film in national parks. Commercial speech traditionally is less protected by the First Amendment.

Recording from public into private spaces

State and federal laws have criminalized some kinds of recordings in public, such as surreptitious videos up people's skirts or down people's blouses.

The "reasonable expectation of privacy" can limit filming into private spaces while in an adjacent public space. Perching yourself in a tree, dangling from a helicopter and using infrared camera technology to "see" through walls or high strength microphones to hear things from a great distance, for example, may cross the line.

Similarly, recording an athlete leaving the field is different from recording the same person visible through a locker room door.

Are there other limitations on recording in public spaces?

The First Amendment also has been seen by courts as protecting recording in public face-to-face conversations when the recording technology is visible; everyone knows they are being recorded, and no one objects.

Recording may require permission

Some states set different legal rules for making audio recordings in public; for example, some two-party states require permission in advance from both the person making the audio recording and anyone being recorded.

Recordings of children almost always require specific permission from parents or guardians. That's why in many presentations, when consent was not obtained, faces will be blurred or voices muted to prevent identification.

Recording criminal activity

Some states ban posting recordings of criminal acts such as murders or violent assaults when the purpose is simply personal gratification or for a commercial purpose. Usually, there is an exception for news reporting.

Recording police officers in public

As a rule, if you are not interfering with the ability of a public official to do their job and the recorded official activity is in public view, the recording is protected by the First Amendment. Police and other government officials typically do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy when on duty.

But limits on recording in public can apply for public safety or security purposes; for example, to keep the public safely away from a fire or to preserve security at a military base.

Remember that the definition of interference varies both on specific facts and from state to state. One state may allow officers to set a crime scene boundary of 30 feet while another might double or triple that distance, and courts will decide what is a reasonable limit.

Police and people making recordings in public often differ on what constitutes interference and what justifies making such a recording for the public good, such as exposing excessive use of force when making an arrest.

Most First Amendment experts advise that even when the person making the recording believes it is a protected First Amendment activity, it's best to follow police commands, if only to preserve all options in court if arrested.

Depending on the circumstances, police can sometimes seize your camera or audio recording equipment. But police generally cannot review recorded material without a search warrant. And they definitely cannot erase it.

RELATED: Everything to know about First Amendment audits

Recording participants in a public protest

You have a right to video record matters of public interest in a public place, such as demonstrations or protests. But note some states criminalize recording audio of conversations without permission, even in public.

Exceptions for recording in public while newsgathering should apply, though these may require a court decision. And interfering with legitimate police activity may warrant limits on recording for newsgathering as well.

Recording public performances

Games and theatrical or movie presentations, even if in a publicly owned or funded space, have a right under copyright law to limit or ban recordings. Look at your ticket: It often says that you are not allowed to photograph or record (for distribution or at all).

Press credentials for such events often have limits too, such as restricting recording or requiring photographers and videographers to let the performer, league or event organizer use the content.

After recording in public, what can I do with the recorded material?

If you post a recording made in public that shows only you or uses only your own voice, you are likely protected by copyright standards and your First Amendment rights.

But just putting yourself into a recording won't always protect taking or posting your recording, depending on what's in the background.

If you do make a recording in public, posting video or audio of copyrighted performances can raise legal issues, even if you intend for only your friends and family to see it on your personal social media site.

RELATED: 10 of the Most Famous Copyright Cases In Pop Culture History

Your intent in posting an otherwise permissible recording made in public also might be subject to a lawsuit if it can be proved in court that your intent in posting was to subject a person shown or heard to "negligent or intentional infliction of emotional distress." And an evolving area of law may well prohibit making or posting a recording if you had a reasonable expectation that it would directly and immediately cause physical harm to someone.

Supporters of such restrictions argue that the ever-increasing speed and immediate reach of cell phone technology coupled with the pervasive extent of social media require new restrictions by government, even for recordings made in public.

Social media sites' terms of service

Each social media site – by virtue of being a private company, not part of the government – can set its own rules and terms, which users agree to (admittedly, in the fine print that most users don't read line-by-line). Those terms of service lay out what can and can't be posted on each site, including public recordings that are legal.

For the most part, social media sites don't distinguish their content guidelines for various kinds of posts. In general, regulations about content apply to photos, videos, audio recordings, GIFs and illustrations.

RELATED: The complete guide to free speech on social media

Recording and earning money

Even when you can legally make a recording in public, each person being recorded retains a right of publicity – a right to control who makes money off their image – that can require a written agreement before use. News recordings in public on matters of public interest generally are exempted.

The bottom line on recording in public

The First Amendment protects freedoms of speech and of the press, which generally includes the right to gather information such as through recording. And in public, people cannot expect privacy. But the ability to record and share recordings of things in public is not unlimited; it often depends on who you are recording, where and for what purpose.

Gene Policinski is a senior fellow for the First Amendment at the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at gpolicinski@freedomforum.org.

How I Exercised My Rights as a Student Journalist

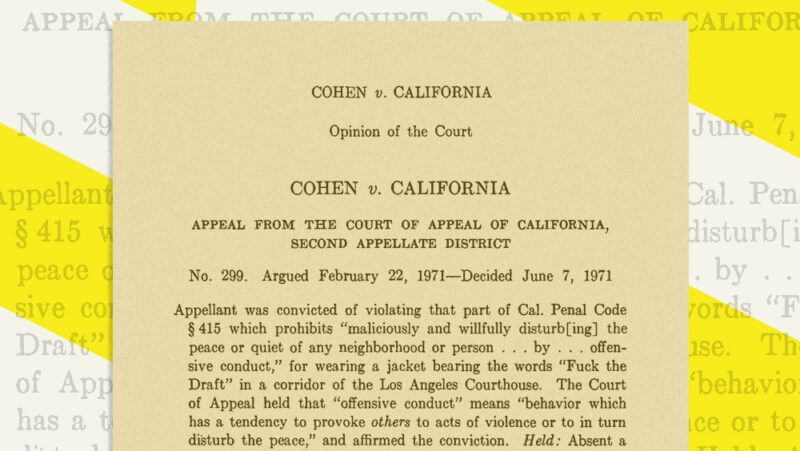

Paul Robert Cohen and “His” Famous Free Speech Case

Related Content

Here to top your best dad joke.