Does Displaying, Teaching Ten Commandments Violate the First Amendment?

The Ten Commandments and the First Amendment often come up together in discussions about American public life. This is because they represent two important but sometimes conflicting ideas: the role of religion in America’s history, and the rule that government and religion should be kept separate. Many people disagree about how to balance these ideas. To understand the bigger picture of how religion fits into American society and government, it’s important to understand how the Ten Commandments and the First Amendment relate to each other.

What are the Ten Commandments?

The Ten Commandments are a set of religious rules that are important in Judaism and Christianity. They come from the Bible and are believed to be rules given by God. Some of the commandments include ideas such as “You shall not steal” and “Honor your father and mother,” though the exact wording may vary between different religious traditions.

What is the First Amendment?

The First Amendment is part of the United States Constitution. It protects freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and the right to petition the government. For this article, we’ll focus on the part about religion. The First Amendment says the government can’t make laws about setting up a religion, and it can’t stop people from practicing their religion.

How the Ten Commandments and the First Amendment relate

Sometimes, people want to use or display the Ten Commandments in public places or in government activities. This often causes problems with the First Amendment. Some people think using the Ten Commandments in public life goes against the First Amendment because it might look like the government is supporting one religion over others. This violates the establishment clause, the part of the First Amendment that prohibits the government from establishing an official religion. Other people think it’s OK because the Ten Commandments are an important part of history and law.

RELATED: What is the separation of church and state?

These different ideas have led to many court cases and arguments. Let’s look at some examples of when this comes up.

Making laws based on the Ten Commandments

Some people think laws should be based on the Ten Commandments. For example, they might say stealing should be against the law because the Ten Commandments say, “You shall not steal.”

When it comes to the First Amendment, things get tricky. The government can make laws that happen to match some of the Ten Commandments, like laws against stealing or killing. But the reason for the law can’t be just because it’s in the Ten Commandments. To follow the First Amendment, laws need to have a main purpose that isn’t religious, even if they happen to agree with religious rules. For instance, laws against stealing and killing are primarily designed to protect people’s lives and property, which is a key role of the government.

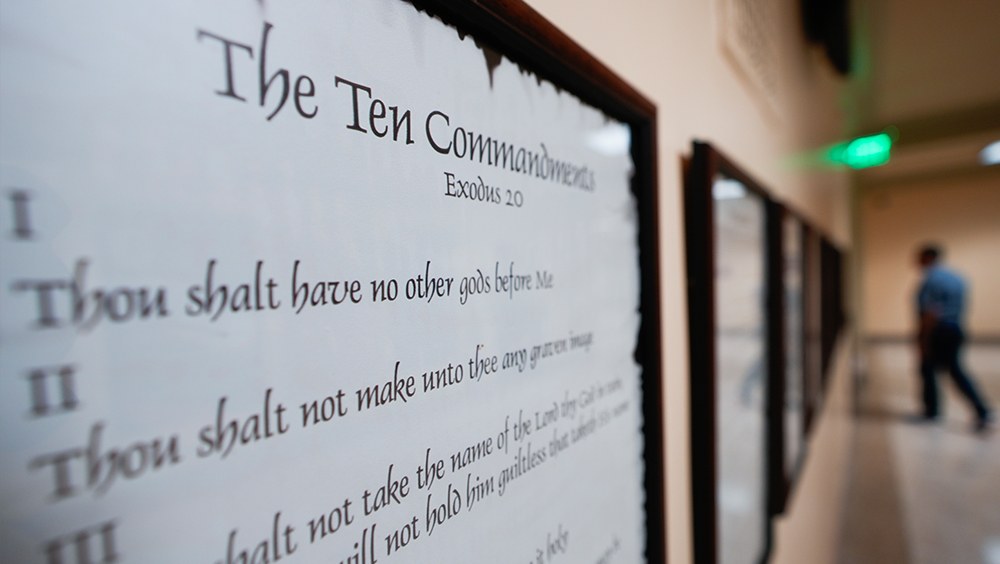

Displaying the Ten Commandments in public places

Sometimes, people want to put up displays of the Ten Commandments in public places like parks, courthouses or other government buildings.

The First Amendment makes this a complicated issue. Courts have said that whether it’s allowed depends on the specific situation. If the display looks like the government is promoting religion, it might violate the First Amendment’s prohibition on establishment of religion. But if the Ten Commandments are shown as part of a larger display about the history of law, it might be OK.

In McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005), the U.S. Supreme Court said that putting framed copies of the Ten Commandments in two Kentucky courthouses was not allowed. It decided this because the main purpose seemed to be promoting religion, which goes against the First Amendment’s rule that the government can’t establish an official religion. The court also said that showing the Ten Commandments is usually seen as religious unless there’s a clear nonreligious reason for it.

That same year, in Van Orden v. Perry, the court allowed a Ten Commandments monument to stay on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol. It decided differently here because the monument had been there for a long time and was part of a larger display about the history of law. This context made it less about promoting religion and more about showing history.

Displaying the Ten Commandments in public schools

Some people have wanted to put up Ten Commandments displays in public school classrooms or hallways. For example, in 2024, Louisiana passed a law requiring Ten Commandments displays in classrooms, sparking renewed debate and legal challenges.

From a constitutional standpoint, this is usually not allowed. Courts have generally ruled against putting up Ten Commandments displays in public schools. The reason ties back to the First Amendment: Young students might think the school is telling them to follow these religious rules. The First Amendment requires schools to be especially careful about not promoting any particular religion.

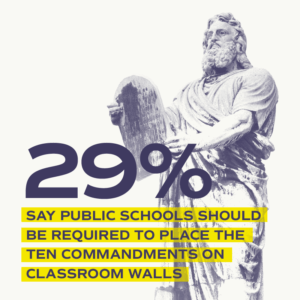

Nearly one-third of Americans say public schools should be required to display the Ten Commandments in classrooms, according to our 2024 Where America Stands survey.

Kentucky tried something similar back in 1978. It passed a law that required every public school classroom to display the Ten Commandments. The displays were to be paid for by private donations, not public money. To try to make this law acceptable, Kentucky said each display had to include this note: “The secular application of the Ten Commandments is clearly seen in its adoption as the fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.” It was hoped this would show that the purpose wasn’t religious but about teaching history and law.

The Supreme Court struck down the Kentucky law in Stone v. Graham (1980). The court’s decision essentially stated that simply calling something nonreligious doesn’t make it so. The court found that the purpose of posting the Ten Commandments was plainly religious and not related to any educational mission. The fact that the displays were privately funded didn’t matter because the state was still requiring the Ten Commandments to be posted.

On Nov. 12, 2024, a federal judge ruled that Louisiana’s law requiring the Ten Commandments in classrooms violates the First Amendment and blocked its enforcement.

Teaching about the Ten Commandments in schools

There’s a difference between teaching students about the Ten Commandments as part of history or literature and teaching students that they should follow the Ten Commandments.

The First Amendment draws a clear line here. It’s usually OK for schools to teach about the Ten Commandments as part of a class on history, literature or world religions. This is considered teaching “about” religion. However, the Constitution doesn’t allow schools to teach that students should follow the Ten Commandments or that they are the true rules to live by. This would be seen as schools promoting religion, which goes against the First Amendment. For example, a history teacher could discuss how the Ten Commandments have influenced some laws in different societies. But a teacher couldn’t tell students they should follow the Ten Commandments in their own lives or that the Ten Commandments are the best rules to live by.

In 2024, Oklahoma’s superintendent of public instruction ordered that the Ten Commandments and the Bible be taught in all public schools for grades five to 12. This order could challenge or support the distinction between teaching about religion and promoting it. The superintendent said this was necessary because the Bible is important to understanding American history and values. However, the order faced opposition. Some school districts refused to follow it after the state’s attorney general said it would break state law. A group of parents and teachers also sued, claiming the order goes against the First Amendment. The case is pending in the courts.

The ongoing constitutional dialogue around the Ten Commandments and the First Amendment

People are still talking and sometimes disagreeing about the role of the Ten Commandments in public life. Courts sometimes must make decisions about new situations involving the Ten Commandments and the First Amendment.

Some people think that the Ten Commandments are an important part of America’s history and should be more visible in public life. They might say that the Ten Commandments helped shape some of our ideas about right and wrong.

Other people worry that giving the Ten Commandments a special place in government or public schools might make people who follow different religions, or no religion, feel left out. They think it’s important to keep a clear separation between government and religion.

These discussions are part of a bigger conversation about the role of religion in public life in the United States. People often have different ideas about what the First Amendment means and how it should be applied to new situations.

Finding our way through tricky legal issues

The relationship between the Ten Commandments and the First Amendment is complex. Courts have made different decisions depending on the specific details of each situation. In general:

- The government can’t make laws just because they’re in the Ten Commandments, but laws can agree with the Ten Commandments if they have a main nonreligious purpose.

- Displaying the Ten Commandments on government property might be OK if it’s part of a larger, nonreligious display, but it depends on the situation.

- Public schools usually can’t display the Ten Commandments, but they can teach about them as part of history or literature classes.

As society changes, people will likely continue to discuss and sometimes disagree about these issues. The goal is to find a balance that respects both religious freedom and the separation of church and state, as protected by the First Amendment.

Asma Uddin is a Freedom Forum fellow for religious freedom.

12 Free Speech Memes That Highlight the Power of Expression

Dissent Is More Than Patriotic. It’s Baked Into the First Amendment

Related Content

2025 Al Neuharth Free Spirit and Journalism Conference

All-Expenses-Paid Trip To Washington, D.C.

June 22-27, 2025

Skill-Building

Network Growing

Head Start On Your Future